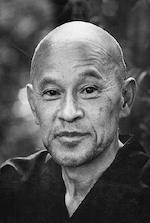

Zazen, Rituals & Precepts Cannot Be Separated Shunryu Suzuki Roshi Wednesday,

July 28, 1970 |

I want to talk with you about some problems you may have when you come

to Zen Center. I think you understand pretty well why we practice. Why

we observe rituals is perhaps more difficult to understand. If you ask

me why I observe rituals, it is difficult to answer. First, I do it because I have been doing it for a long time so there is no problem. I tend to think that because I have no problem in observing my way, then you must not have a problem [laughs]. But you are Americans, and I am Japanese, and you have not been practicing the Buddhist way for so long, therefore there must be various problems [laughs]. These problems are almost impossible to solve. But if you actually follow our way I think you will have some understanding of our rituals. What I want to talk about is the precepts. Precepts for me includes rituals. And when we say "precepts," it is another name for our zazen practice. For us, zazen practice and observation of rituals are not two different things. How to observe the rituals is how to observe the precepts. Our practice, especially in the Soto school, puts emphasis on everyday life, including rituals, eating, and going to the restroom. All those things are included in our practice. |

|

So the way we practice zazen, the way we practice rituals, and the way

of life of a Buddhist or Zen student is all fundamentally the same. But

when we talk about our way of life or rituals, we come face to face with

some rules. The rules of observing ceremonies are rituals, and the rules

of our everyday life are our precepts. When we say "precepts," we

usually mean some rules, but that is just a superficial understanding of

precepts. Precepts are actually the expression of our true nature. The

way we express our true nature is always according to the place or

situation in which you live. So to practice zazen is to be yourself and

to observe our precepts is just to be yourself. As you have some way of sitting on a black cushion, we have some way of observing our rituals or ceremony in the Buddha Hall. The point of our zazen practice is to be free from thinking mind and from emotional activity. In short, that is the practice of selflessness. In our observation of rituals, the point is to be free from selfish ideas. The practice of rituals is the practice of selflessness. First you enter the room and you bow. In Japanese we say gotai tochi. Gotai is "our body." Tochi is "to throw away." It means to throw away our physical and mental being�in short, to practice selflessness. We offer ourselves to Buddha. That is the practice of bowing. When you bow [to the floor], you lift your hands. We lift Buddha�s feet, which are on your palms and you feel Buddha on your palms. So when you practice bowing, you have no idea of self. You give up everything. When Buddha was begging, his follower spread his hair on the muddy ground and let Buddha walk over it. That is supposed to be the origin of why we bow. In ritual, you bow and work. You begin everything by some signal. That kind of thing you may not like so much [laughs]. It looks very formal, to begin everything by the sound of a bell. Whether you want to do it or not, you must do it. It looks very formal. As long as you are in the Buddha Hall, you should observe our way according to the rules we have there. We do it to forget ourselves and to become one. To be a Zen student in this Buddha Hall is why we observe our rituals. This is a very important point. To feel your being, here, in this moment, is a very important practice. That is the point of observing precepts and observing rituals and practicing zazen. To feel or to be yourself at a certain time, in a certain place. That is why we practice our way. So the actual feeling of rituals cannot be understood without observing them. When you observe them, you have the actual feeling of rituals. As long as you try to know what it means or why you do it, it is difficult to feel your actual being in this place. Only when you do it will you feel your being. To be a Buddhist is to do things like Buddha. That is actually how to be a Buddhist. It does not mean that when you are able to observe our rituals as your friends do, that you will have no problem in your everyday life. This ritual feeling, or practice, will extend into your everyday life. You will find yourself in various situations, and you will intuitively know what you should do. You will have the right response to someone�s activity. When you are not able to respond to another without wondering what he has on his mind, you will force something. Most of the time I don�t think you will give the most intuitive response. I want you to do rituals until you are quite sure about your response to other people. How one responds to others is very important. When we teachers observe our students, they may be trying to act right, and trying to understand people, but most of the time it is rather difficult for them to have some kind of intuition. If you start to have this kind of intuition, you will have big confidence in yourself, and you will trust people, and you will trust yourself. And so, all the problems which you created for yourself will be no more. You will have no more problem. That is why we have training or practice. My master, Gyokujun So-on, used to say, "Stay with me for several years. If you become a priest, you will be a good priest, and if you remain a layman, you will be a good layman or good citizen, and you will have no problem in your life." I think that was very true. I was the sixth and youngest disciple when I became my master�s disciple. Two of us became priests, the rest of the disciples remained laymen. They are very good actually. When they came to my teacher [laughs], they had some trouble. Except for one disciple who passed away, the rest of them have done pretty well, although they are not priests. So I think what he said is very true. This is very good practice for you. You may think our practice is like army practice [laughs], but actually it is not so. The idea is quite different. I think the Japanese army copied our practice. It looks like it, but they couldn�t copy our spirit. You should trust your innate nature, your buddha-nature. That is the most important point. If you trust your true nature, you should be able to trust your teacher, too. That is very important. Not because your teacher is perfect, but because his innate nature is the same as yours. The point of practice between teacher and disciple is to get rid of selfish ideas as much as possible and to trust each other. Only when you trust your teacher can you practice zazen, can you practice rituals, and can you act as a Zen Center student. To remain always a Zen Center student is a very important point. You become a Zen Center student by trusting your true nature, and trusting your teacher, and trusting your zazen practice without saying why [laughs]. I think you should do it, as long as you come here. And if you don�t want to do so, I think you shouldn�t come here. As long as you come here, you should follow our way, or else maybe you will waste your time and you will regret it. So in this way, we can carry on our schedule. The way we carry on our schedule is the way we observe our precepts. Precepts were initiated by Buddha when he said, "Don�t do this, or don�t behave like that." That was the origin of precepts. In India, in Buddha�s time, there were Buddha�s precepts. And in China, they have precepts which are based on the Chinese way of life. We have sixteen precepts, and these precepts are the essential precepts which we should observe as a Japanese, as an American, or as an Indian priest or layman. These precepts are the precepts which you can apply to your everyday life. We say, "Don�t kill," but "don�t kill" does not just mean don�t kill flies or insects. Actually, it is too late. If you say, "Here is a fly, should I kill it or not?" it is too late! Before we see the fly, we have this kind of problem. When we eat, we say, "Seventy-two labors brought us this rice." When we say "seventy-two labors" this includes protecting grains from various insects. It is not just�not to kill insects. When you eat, and you chant, "Seventy-two labors brought us this rice," it includes already the precept of "not to kill." After making a great effort to protect the corn from insects, we can eat. When you chant, "seventy-two labors," you should be relating to the precept "not to kill." So "not to kill," is not any special precept. To exist here in this way is the result of sacrificing many animals and plants. You are always sacrificing something. So as long as you are involved in dualistic concepts, it is not possible for you to observe our precepts. So how to get out of dualistic concepts and fill our being with gratitude is the point of practice. Actually it is very foolish to say "not to kill." But the reason we say "not to kill" is to point out or to understand our life from various angles. Not to kill, not to steal, not to speak ill of others. Each of these precepts includes the other precepts. And each practice or ritual we observe includes the others. So if you have the actual feeling of being here, that is the way to observe precepts and the way to practice zazen. If you understand how you observe even one precept, you can observe the rest of the precepts and you can practice zazen, you can observe rituals. Zazen practice and observation of rituals or precepts cannot be separated. How to experience this kind of feeling is how you understand our precepts. If you say it is difficult, it may be very difficult. But it will not be so difficult a thing if you say, "I will do it." That is how you observe precepts, even without thinking whether you can observe them or not. "I will do it" means "don�t kill animals." You may say so, because originally it is not pos-sible to kill anything. You think you killed, but actually, you cannot. Even though you think you killed, they are still alive [laughs]. Even though you eat something, it is still alive in your body. If something leaves your body, it is still alive.It is not possible for anything to be killed. The only way is to be grateful for everything you have. That is how we keep our precepts without having a dualistic understanding of precepts. Then you may say, "If so, there will not be any need to have precepts." But unless you are sure, you cannot feel your presence or your being. You do not feel you are alive. You do not have the joy of life or gratitude for everything. You can easily say, "No, I wouldn�t kill anything." But it means that you will not sacrifice yourself for anything. You will be just you. You will not be caught by a dualistic understanding of yourself, and you will feel yourself, as you feel yourself in zazen. It is rather difficult to explain, but that is actually how we observe precepts. Dogen Zenji said, "Even though we do not try to observe precepts, like a scarecrow [laughs] more evil comes to you." It is strange, when you feel your being in its true sense right here, no evil comes. You cannot violate any precepts, and whatever you do, that is the expression of your true nature. You will not say, "I shouldn�t say that," or "I shouldn�t do that." You will be quite free from that kind of regret or arrogance of observing some special precepts. That is how to observe precepts. To repeat, precepts are chewing your brown rice [laughs]. Without chewing your brown rice, you cannot eat it. Only when you chew it for a pretty long time will you appreciate the taste of brown rice. When you say, "Oh this is awful! [Laughs] how many times should I chew it before I swallow it down?" that is a very foolish way of eating brown rice. If you say, "Oh, sixteen precepts! Awful to be a Buddhist!" [laughter] Then you have no chance to have a real taste of the Buddhist way. If you observe them one by one, that is how you chew brown rice and how you practice our way. � Copyright San Francisco Zen Center 2000 |

|