|

The opening lines of the Tenzo

Kyokun, or Dogenís Instructions for the Cook, go like this: "From ancient times, in communities practicing the Buddhaís Way, there

have been six offices established to oversee the affairs of the community.

The monks holding each office are all disciples of the Buddha and they all

carry out the activities of a Buddha through their respective offices.

Among these officers is the tenzo, who carries the responsibility of

preparing the communityís meals. Dogen says that, in the past, the work of the Tenzos and other officers in the monastic community was carried out by teachers "settled in the Way." If you go to a large monastery like Eiheiji, these officers are usually roshis or mature teachers. In the case of the Tenzo, because so many people work in the kitchen with him or her as teacher, the office is rather special. The group working with the Tenzo in the kitchen is like a small community in itself. At Tassajara [S.F. Zen Center's monastery, near Carmel, California], for example, seven or eight people work together all day, every day, in a very confined space. |

|

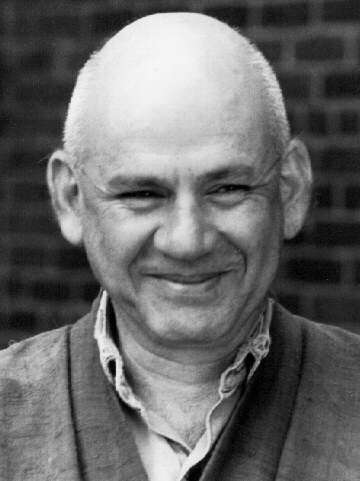

Lecture by Sojun Mel Weitsman Roshi on Day one of a Meditation Intensive (Sesshin) in December, 1993 Reprinted from the Berkeley Zen Center Newsletter |

|

|

In a young practice such as ours, we canít always find a roshi to be Tenzo. Often the Tenzo is not as mature a person as ideally we would like to have. It is, though, a great training position for someone. You have to have some maturity. The Tenzo should be a teacher for others. But sometimes others are a teacher for the Tenzo. It goes back and forth. It requires an open and non-opinionated mind. Sometimes not knowing anything is best. Dogen stresses this in his essay. He says, "Such a practice requires exhausting all your energies." And it does. It can be a tiring job. The Tenzo works long hours and can easily get burned out. Anyone working in the kitchen long hours needs to find a rhythm for their work. This way they can find their ease within the work itself. This is true of all our activities. It is certainly true of zazen. Usually we work hard, then rest; then work hard again, then rest again. But when you engage in a continuous activity over a long period, you have to find your rest and your ease within the activity itself. Otherwise you canít sustain yourself. This is the koan of work. It is also the koan of zazen. When we sit sesshin all day, we put out a lot of effort. We have to find our ease within that effort. We are totally engaged in hard effort, but, at the same time, there is a letting go of the tensions and anxiety that build up, a letting go of thinking ahead too much. The practice of the Tenzoóor of anyone working in the kitchen, or anyone sitting zazenóis how to be present, fully present, moment by moment, without being caught by either past or future, or like or dislike. Working in the kitchen and sitting zazen are not different things. When someone cooks all day for the Sangha, this is kitchen sesshin. Itís not just cooking. Itís just cooking. Itís not just turning out meals, itís non-dual practice, the practice of big mind. Dogen says, "If a person entrusted with this work lacks such a spirit, then that person will endure unnecessary hardships and suffering that will have no value in their pursuit of the Way." This is not like an ordinary person going to work. That person works hard, sits down, takes a rest, and says, "Iím glad that is over." Then he or she might read a newspaper or something. What Dogen is talking about is not like that. When working maturely, the way Dogen is talking about, one gets tired of course, but there is a certain quality of the work that is beyond being tired or not being tired. A certain joy arises with the total effort Dogen has in mind here. If you just see it as a job, you may find yourself in misery. "Put your awakened mind to work," Dogen says. How is this practice done? How do we carry out our activities without giving way to attachment and emotional entanglements? The book from which I am reading is From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment, Refining Your Life. Itís a cookbook, but itís not about recipes. Itís a cookbook about the person doing the cooking. As we prepare the meals, we are being cooked and prepared and refined. This is the important point. Someone may be a very fine chef, but that person is not necessarily the right person to be the cook in the monastery or practice place. The real point is whether one engages in this kind of activity as a refinement of oneís own life. Someone may say, "I worked in the kitchen the whole sesshin," and not understand that to cook the food is to cook yourself. To prepare the food is to prepare yourself. To refine the food is to refine your own practice. Suzuki Roshi used to talk about finding your composure and being settled. He spoke of it as "being settled on the self." Being settled on your self means never losing your composure. This is more than just having some false way of holding yourself. It means not being pulled off your place by anything. Not reacting to someoneís anger, not reacting to someoneís emotions, or feelings, or ideas, in a way that pulls you off your place. It also means taking good care of things, not just of yourself, not just of the people around you, but of your whole environment. Finding your true composure means being one with your environment. When you are working in the kitchen, that is your whole world. Everything in it is your world. How you take care of each thing and each person is important, including how you prepare the meal and how you think about it. The same is true of everything else. How a server serves the meal, how someone uses their oryoki [a monkís eating bowls] to eat the meal. All these activities are tools for refining your life. Dogen talks next about a Tenzoís typical day at the monastery. The Tenzoís day starts after the noon meal, when he or she convenes with the director and assistant director. Together the three plan the meals for the following day. Once this is done, the Tenzo sets about obtaining the necessary ingredients. Dogen says: "Once he has these, he must handle them as carefully as if they were his own eyes." Dogen dignified even the most common things. For Dogen it was important to treat everythingóthe pots and pans, the foodóvery carefully and with great respect. When someone acts in this way, there is no gap between subject and object. There is no gap between the one who is preparing the meal and that which is being prepared. This is the enlightened activity of the Tenzo, the enlightened activity of one who works in the kitchen. Working in this way is not just a job, it is an opportunity. It is a great opportunity for expressing enlightenment. You may feel, "But, Iím not enlightened yet, so how can I do that?" If you participate in your work the way Dogen is suggesting, enlightenment will express itself. In our practice, it is very important to realize that weíre not working from delusion to enlightenment. Enlightened activity is something you can express right away. When you express enlightened activity, enlightenment is everywhere. When you donít, itís not. To practice in Dogenís way, just step right in, right into practice-enlightenment. This, incidentally, is why itís possible to sit zazen without knowing anything. When you sit zazen, you just step into enlightened practice. You can practice enlightened practice right now. Just be one with your activity, completely. Donít separate subject from object. Even though vegetables are vegetables, the knife is the knife, and you are you, cutting vegetables can be cutting it all into one. Stirring the soup can be stirring the soup into one. Stirring the soup can be stirring in complete stillness. Dogen continues: "You must not leave the washing of rice or the preparation of vegetables to others, but must carry out this work with your own hands." Today, the Tenzo doesnít usually do this. Things have changed since Dogenís time. The Tenzo mostly oversees, does the ordering and so forth. Still Dogen is saying, "This is your responsibility." Even if someone else does it, youíre responsible. You shouldnít simply assign something to someone and ignore it. Put your whole attention into every aspect of your work and see just what the situation calls for. Do not be absent-minded in your activities, and do not be so absorbed in one aspect that you fail to see its other specifics. This raises the issue of concentration. Sometimes we think of zazen as concentration. If you ask, "What is zazen?" some people will say, "Concentration." It is true that concentration is present. But if you become overly focused on some small part and cannot see the rest, that is not proper concentration. You must be focused on your activity, and at the same time be aware of the larger picture. Sometimes when people are working in the kitchen, they work very slowly, self-absorbed in their own activity, believing that if they work slowly, that is concentrated activity. But you must be concentrated and quick as well. You must be, mindful of when the meal has to be finished and aware of what other people are doing. You must be aware of how you are harmonizing with everyoneís activity so that at some point it all comes together and makes a meal. That is the necessary kind of concentration. Hereís an example. Sometimes a server walks very slowly with the pot, thinking that this is concentrated activity. But this can make people anxious. When a server is too slow, people think, "Are they ever going to get here?" A server should actually walk briskly. However, not too briskly, not too fast. If a server walks too fast, people can get agitated. Then the people eating might think, "Iíd better hurry up so I can finish before they get here." Itís can be very upsetting! So, a server should walk briskly. Not too slow, not too fast. When you walk in the zendo as a server with your food offering, you are creating an atmosphere. That atmosphere should be appropriate for whatever activity is going on. For instance, when you enter the zendo during zazen, you should walk very slowly, so you donít disturb peopleís zazen. This is different than when you are serving. When we serve, we should walk briskly, so people feel there is movement and donít get anxious. When there is zazen, we should walk slowly so as not to disturb the air. This is enlightened activity. When you donít ignore what is going on, and you donít just push your own idea, then whatever is creatively coming forth from you will come forth naturally without disturbing the situation. It will add to the situation. Each one of us adds to the situation. For instance, when you go to sesshin you might think, "Oh, thereís this sesshin these people have set up and Iím simply coming to it." But actually it is you who create sesshin when you step inside the gate. In the same way, when you step into the kitchen, you contribute to the atmosphere there. Everyone counts. Everyone is responsible. Each one of us has a part in what is going on. This is what Dogen means when he says, "Do not overlook one drop in the ocean of virtue by entrusting it to others. Cultivate a spirit which strives to increase the source of goodness upon the mountain of goodness." When you do things correctly, itís powerful. It moves things toward composure and stability. Dogen continues: "In Regulations for a Zen Monastery we find, ĎIf the Tenzo offers a meal without a harmony of the six flavors and the three qualities, it cannot be said that that person serves the community.í" The six flavors are bitter, sweet, sour, salty, hot, and mild. Certain personalities go with these flavors. Some people are sweet, some people are sour, some are hot. Iím salty. Iíd rather eat bread than cake. Bread is salty, cake is sweet. The three qualities or virtues are "light and flexible," "clean and neat," "conscientious and thorough." These are qualities we should cultivate. Light and flexible means that you are not stiff, not stuck. You have the ability to bend with things. That is important since it is the brittle things that get broken. Clean and neat means to clean up as you go, so that when you finish your preparation, you leave no trace. You donít leave a sink full of dishes, for example. Each thing is taken care of completely. Conscientious and thorough is like eating with oryoki. In fact, oryoki training is good training for working in the kitchen. When eating oryoki, you take care of each article, each thing is conscientiously washed and put away. If you do oryoki completely, every moment flows easily into the next with no unnecessary motion. Done in this way, Oryoki is enjoyable. Sometimes people say, "I donít enjoy oryoki at all." I think this happens when a person doesnít understand the process of having one movement flow logically into the next. When one does oryoki with this flow in mind, then it doesnít feel mechanical. Itís a wonderful feeling, moving smoothly and experiencing that coordinated activity. The teachings Dogen presents in Instructions for the Zen Cook are not just about the kitchen. We need to think about all of our activity in this way. All of our activity can be shikantaza ["just sitting"]. * All Tenzo Kyokun quotations from the translation by Thomas Wright in Refining Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment (NewYork: Weatherhill, 1983). © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2002 |

|