|

Zazen is vast openness, completely

opening ourselves and accepting whatever we are experiencing. It’s nice to be in this place, on this particular spot in the universe. Somehow, all of us are together on this particular spot in the universe. It’s quite a wonderful thing. I don’t know how it happened. Quite a diverse group of people – some of you come from different practice backgrounds, and yet we are all able to do this practice together without any problem. Today I want to look at Dogen Zenji’s teaching, the Genjo Koan. Near the end he says, “A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims, there is no end to the water. A bird flies in the sky, and no matter how far it flies, there is no end to the sky. However, the fish and the bird have never left their elements since the beginning. When their activity is large, their field is large. When their need is small, their field is small. Thus, each of them totally covers its full range, and each of them totally expresses its realm. If the bird leaves the air, it will die at once. If the fish leaves the water, it will die at once. Know that water is life and air is life, the bird is life, and the fish is life. Life must be the bird, and life must be the fish. It is possible to illustrate this with many more analogies. Practice, enlightenment, and people are all like this.” |

|

Zazen is Vast Openness

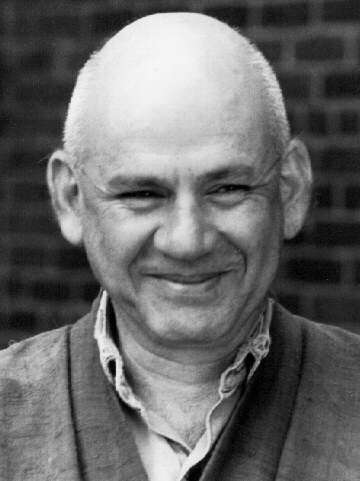

Sojun Mel Weitsman Talk given to the Chapel Hill Zen Center, March 1993 |

|

|

Here Dogen is talking about our human situation and Buddha nature. Each one of us is like a fish or a bird in the vast sky of Buddha nature, or the deep ocean of Buddha nature. So he is talking about how we exist, how each one of us exists, in Buddha nature, as Buddha nature. A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims, there is no end to the water. He is saying, Buddha nature is vast and has no special shape or form, but the fish is the form of Buddha nature. The bird is the form of Buddha nature, and the fish swims in its element. The bird flies in its element, which is Buddha nature. Each one of us swims and flies in our own element. Even though we feel that we don’t know what Buddha nature is, or maybe we feel estranged from Buddha nature, we have never left it from the beginning. He says, “A fish swims in the ocean, and no matter how far it swims, there is no end to the water. A bird flies in the sky, and no matter how far it flies, there is no end to the sky. However, the fish and the bird have never left their elements since the beginning. When their activity is large, their field is large. When their need is small, their field is small. Thus, each of them totally covers its full range, and each of them totally expresses its realm.” In other words, in order to experience the sky completely, when you need to go far, you go far. When you don’t need to go so far, you don’t go so far. But whether you go far or stay in a small space, you experience the whole sky, or the whole depth of the water. If the bird leaves the air, it will die at once. If the fish leaves the water, it will die at once. So you should know that water is life, and air is life. The bird is life and the fish is life. Life must be the bird and life must be the fish This is like the Heart Sutra saying, “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” You can’t tell which is which. You can’t separate them and say, “This is my self, and this is Buddha nature.” Buddha nature is my self. My self is Buddha nature. The sky is the bird, the bird is the sky. The bird can’t leave the sky, and the sky is the bird, and the bird is the sky. The bird is life, and the fish is life. Life must be the bird, and life must be the fish. You can illustrate it in various other ways. When he says, “Thus, each of them totally covers its full range,” another way to translate it is that, wherever you stand, you don’t fail to cover the ground.” What we are doing in zazen is just covering the entire ground. You may be in one little spot, yet this little spot that we cover is the entire ground–the whole ground. Whether it’s tiny or big, we don’t fail to cover the whole ground. This is why zazen is not just some ordinary activity. It is ordinary, but it is ordinary activity that covers the whole ground. Now, he says, “If a bird or a fish tries to reach the end of its element before moving in it, this bird or this fish will not find its way or its place.” If you try to understand everything before you do it, you never get around to doing it. If you feel that you need to know something about zazen before you do it, you can never do it. If you feel, “Oh, I must be better before I do this” or, “I must give up eating meat before I sit zazen,” you’ll never get around to zazen. If you feel that you can know the limit of understanding through your thinking mind, you will never get around to experiencing your True Self. So it is important, actually, to be a little bit stupid. If you know too much, or if you feel that you can know something, then you put a stumbling block in your way. In order to practice and experience Buddha nature directly, you have to give up all of your ideas. Rational mind, thinking mind, or accumulated knowledge, won’t help much, and usually is a hindrance. Your usual way of figuring out what to do won’t help when your legs become very painful. You can’t figure out how to get out of it. You just have to give up. Before we get it all figured out, we just start moving in it. This is the advantage of practice. You can actually practice and experience enlightenment without understanding or knowing anything about it. So it’s wonderful that we can do this. All we have to do is just step in. If you want to know how to swim and get to the other side of the ocean, there is no way you can figure it out, you just step in and start swimming. When you find your place, right where you are, practice occurs actualizing the fundamental point. “Finding your place right where you are” means to really completely be right where you are, on your spot, in any activity. This is actualizing the fundamental point. “Actualizing the fundamental point” is one way to translate Genjo Koan. “Genjo” means actualizing in the present–something appearing right here, right now. The “ko” of “koan” means “to level” which stands for “nature” or Buddha nature. Buddha Nature is very level, no bumps, no special characteristics, no identifiable mark. The “an” of “koan” means “the place,” some given place, some position which Dogen called “dharma position” (or juhoi) At any one moment, everything in the universe is in its dharma position. There are two aspects of the word “dharma.” “Dharma” with a capital “D” means the law or reality, that is Buddha’s law or Buddha’s teaching. Dogen uses it to mean the way things are as fundamental reality. “Dharma” with a small “d” means “things.” Anything and everything is a dharma. Every phenomenal thing is a dharma. So Dharma with a capital “D” is the reality about the dharmas with a small “d.” The “thing” about the things. Everything has its dharma position within Buddha nature, and, from moment to moment, that dharma position changes. Within reality, within undifferentiated reality, all of these dharmas are coexisting, interrelated, and moving, and we call it our life. How we find our dharma position on any moment within ultimate reality manifesting right now, that is our Zen practice. That’s called Genjo Koan, the koan of moment-to-moment everyday life. This is how we deal with our phenomenal position within the vastness of Buddha nature. So Dogen says, “When you find your place (your dharma position), right where you are, that’s where practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point. When you find your way at this moment, practice occurs, actualizing the fundamental point; for the place, the way, is neither large nor small, neither yours nor others’. The place and the way have not been carried over from the past, nor are they merely arising now. Accordingly, in the practice-enlightenment of the Buddha way, meeting one thing, is mastering it – doing one practice is practicing completely.” “When you find your way at this moment, practice occurs.” So time is very important. This moment, moment after moment is very important. In order to practice Genjo Koan, we must be aware of our activity in each moment. When we sit zazen, our life takes place moment by moment, right now. This is our dharma position which arises in the present, on this moment. So the moment is continuous and, at the same time, discontinuous. We sit for forty discontinuous moments; but, at the same time, we are actually sitting for one continuous moment. When you think, “I only have twenty minutes left before the end of the period,” you have left your dharma position, because your dharma position is right now, with no past and no future. Your dharma position exists as just this moment’s activity. So we sit for one “right now.” “Right now” means any moment is “right now.” There is no dividing of the moments, even though we sit, or we exist, from moment-to-moment, one breath at a time. So continuous time and discontinuous time are at the same time, but, when we sit, we are only aware of continuous time, which is called, “right now.” As we sit, we come up with the problem of discomfort. One of the problems that we have is we feel that discomfort or pain is an enemy, something to be conquered or done away with. But pleasure and pain don’t exist independently. Even though we say this is pleasure and this is pain, pleasure and pain don’t exist independently. Because we divide them into pleasure and pain, we feel that one is desirable and the other is not. This is the world of pleasure and pain. It is not the world of pleasure only, although we would like it to be. We really wish that it was the world of pleasure only, and so we orient our life to try and make everything as pleasant as possible, but it doesn’t work because life is both pleasure and pain, and it is both birth and death. We would also like to conquer death, or eliminate it. But in the same way that it is pleasure and pain, it is also the world of birth and death. So on each moment, there is being born and dying. We are being born on each moment and dying on each moment. We have to accept our coming to life and passing away on each moment. This is called nonattachment, and it is also called nonduality, because within our life there is death–at the same time. This moment will never arise again, even though there is nothing but this moment. In order to be comfortable in this world, one needs to accept reality. As long as we don’t accept reality, we are always uncomfortable, even though reality is uncomfortable too. But that is not as uncomfortable as not accepting reality. To be able to experience the pain and the pleasure of life at the same time, doesn’t need to be masochistic: within the pleasure is pain, and within the pain there is pleasure. Being masochistic means that you always want to keep creating some painful situation: that’s not the same idea. What it comes down to is forgetting all about pleasure and pain, just accepting the feeling you have. As soon as we start to discriminate and fall to one side or the other, as soon as we want to have one and not have the other, it’s pretty hard. It is hard to keep our practice pure. Keeping our practice pure means not falling into the duality of craving for one thing and disliking the other. When we sit zazen, we don’t try to create some wonderful, special, desirable state of mind, and we don’t try to eliminate some distasteful thing. Just accept everything as it is. When there are painful legs, it is just painful legs. When there is a pleasant feeling, it is just a pleasant feeling. You may think that when there is no feeling at all this must be the enlightenment they were talking about, but this is just another state of mind. States of mind are continually changing, and there is no special state of mind which is the “right state of mind” that you are seeking. The only thing that you are seeking is nondiscrimination, which is not a state of mind. It is merely giving up craving and rejection – not hanging onto anything and not pushing away anything. Pushing away, or aversion, is also a form of attachment. Whatever we push away, we become attached to. The wonderful thing about zazen is, not that you feel euphoric, but that you allow yourself to sit in reality. When you can sit in reality without grasping or rejecting, hating or loving, then of course you have joy. That is a very joyful experience, but we have to let ourselves experience whatever comes, to be open to everything. Zazen is vast openness, completely opening ourselves and accepting whatever we are experiencing. Our tendency, of course, when something undesirable comes, is to tense up, or push away, so we have to let go of that instinct to close down or fight. The mind should be able to encompass everything. When we find some discomfort, just immediately open to it. So, instead of closing down, we just get bigger. We have to learn how to open our mind completely. Then we have some comfort, but our comfort includes both sides. So, Dogen says, Accordingly, in the practice-enlightenment of the Buddha way, meeting one thing is mastering it. Actually, to meet one thing, just take care of that one thing. Fortunately when we sit zazen, we are just taking care of one thing. Just take care of that one thing, and master it. If you can do that, then you master everything. You don’t have to conquer the whole world piece by piece. Doing one practice is practicing completely. The whole body-and-mind is together with the universe. There’s no gap. “Here is the place, and here the way unfolds. Right here is the place to do it, and right here is where the way unfolds. The boundary of realization is not distinct, for the realization comes forth simultaneously with the mastery of Buddha Dharma. “Do not suppose that what you realize becomes your knowledge and is grasped by your consciousness. Although actualized immediately, the inconceivable may not be apparent. Its appearance is beyond your knowledge.” Even though we don’t know everything and don’t even realize what we do realize, our practice is complete when we sit with a pure and nondiscriminating mind. So, you may not even know the complete meaning of your practice. Dogen then gives an example, Zen master Baoche of Mount Mayu was fanning himself. A monk approached and said, “Master, the nature of wind is permanent, and there is no place it does not reach. Why then do you fan yourself?” “Wind” here means Buddha nature. He is saying, if Buddha nature is all-pervasive and there is no place where it is not, why are you fanning yourself? It is a good question. This was Dogen’s question when, as a young monk, he went to China. Dogen said to himself, “If everybody has Buddha nature, if Buddha nature pervades the universe, why do you have to do anything?” So, he went to China with this in mind: Why, if Buddha nature is everywhere, why are you doing something about it? Why are you fanning yourself? Baoche replied, “Although you understand that the nature of wind is permanent, you do not understand the meaning of its reaching everywhere.” “What is the meaning of its reaching everywhere?” the monk asked again. The master just kept fanning himself. The monk bowed deeply. What is the nature of “permanence?” The master’s fanning means, even though the nature of wind is permanent, in order to experience that, or in order to understand it, you have to do something. You can’t just lie back. You have to do something. You have to actualize Buddha nature or realization through activity. Even though the nature of everything is Buddha nature, and Buddha nature is all existence, in order to realize what it is, we have to do something. For example, in order to get a cake, although all the ingredients are there, you still have to put the ingredients in a bowl and mix it up, and put it in the oven. Otherwise you have no cake. Why do we practice? Why do we have to do this? Why do we sit with our legs crossed? Why do we study, if everything is right here now? Dogen’s whole understanding of practice is that practice and realization go together. In order to realize your true nature, you have to realize it through practice, you actualize it through your practice activity. Therefore, Dogen says practice is not different than enlightenment, and enlightenment is not separate from practice. That is why he says some may realize it and some may not: even though realization appears through practice as practice, and practice appears as realization, you may not recognize that. But if you practice, realization is there. Then he continues: “The monk bowed deeply. The actualization of the Buddha Dharma, the vital path of its correct transmission is like this. If you say that you do not need to fan yourself because the nature of wind is permanent, and you’re going to have wind without fanning, you will understand neither permanence, nor the nature of wind. [In other words, you won’t understand Buddha nature, and you will also not understand your own activity, even though you think you understand your activity.] The nature of wind is permanent. Because of that, the wind of the Buddha’s house brings forth the gold of the earth, and makes fragrant the cream of the long river.” There are many important points, but I think the important point here is how to bring to life, our life on each moment, and, in this way, to extend zazen into our daily life by finding our dharma position on every moment within the realm of reality. It means no self-centered activity. Just basically not to be selfish. That is very simple. To find our place, our dharma position, within the realm of Buddha nature, moment by moment is to not have any self-centered activity. As soon as we revert to self-centered activity, we lose our dharma position. We lose our way and our place. But as long as we continue this non-self-centered activity, the way and the place open up wherever we are. There is no special thing that we have to do, but everything we do is very special, special in the sense that it’s real. Sweeping the floor, washing the dishes, just ordinary activity becomes the Way. Transcribed by Patti Fogg © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2005 |

|