|

Excerpts from a talk given at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, October 13, 1991, during a two-week intensive training sponsored by Sotoshu Shumucho, the headquarters of the Japanese Soto Zen Sect, which was attended by thirty Soto Zen teachers from Europe, Brazil, Japan, and the US. This historic meeting was the first time Western representatives of Soto Zen lineages met officially with their Japanese counterparts outside of Japan. I feel that there is a koan that epitomizes our situation with Japan and the Shumucho at the moment. This is Case #61 in the Blue Cliff Record, Fuketsuís "One Particle of Dust." There are various ways of approaching this koan, so please give me the space to interpret it in this way. Engo intro-duces the koan saying "Setting up the Dharma banner and establishing the Dharma teachingósuch is the task of a teacher of profound attainment. Distinguishing a dragon from a snake, black from white, that is what the ma-ture master must do. Now let us put aside for a moment how to wield the life-giving sword and the death-dealing blade, and how to administer blows with a stick. Tell me, what does the one who lords it over the universe say?" The main case: Fuketsu said to the assembled monks, "If one particle of dust is raised, the state will come into being. If no particle of dust is raised, the state will perish." Later on, Setcho, holding up his staff, said to his disciples, "Is there anyone among you who will live with him and die with him?" And then Setcho has a verse. "Let the elders knit their brows as they will. For the moment, let the state be established. Where are the wise statesmen, the veteran generals? The cool breeze blows; I nod to myself." Raising a particle of dust is a way of saying "starting a practice place." Start-ing a place like Tassajara is raising a speck of dust. Zen Center is a speck of dust. Los Angeles Zen Center is a speck of dust. Eiheiji is a speck of dust. If one raises a speck of dust, the state will come into being. If we donít do something, it wonít happen. So the question is, what should we do? This was Suzuki Roshiís koan. Suzuki Roshi had been invited from Japan to Sokoji Temple in San Francisco to take care of the Japanese congregation. Many Western Americans started to sit [zazen] with him. He invited people to sit with him and Zen Center sprang into existence. That was the first speck of dust. It just happened. But in deciding to do something, you donít know whatís going to come up along with this speck of dust. I heard one time that when we were buying the building in San Francisco on Page Street Suzuki |

|

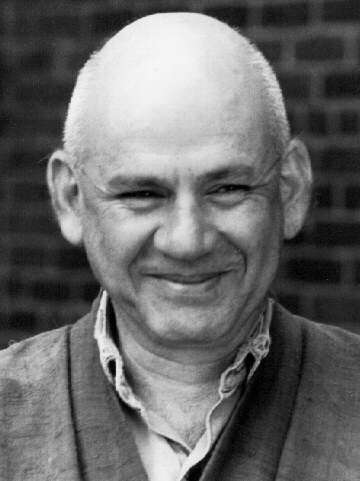

Raise a Speck of Dust, Reunite the Dharma Family by Sojun Mel Weitsman |

|

|

Roshi said, "Iím so nervous, so anxious about this that I donít know whether Iím going to the bathroom in the sink or washing my face in the toilet." Setcho later holds up his staff and says to his disciples, "Is there anyone among you who will live with him and die with him?" The first part, raising a speck of dust, is to decide to do something. The second part, to "live with him and die with him," is how do you maintain it? How do we know what weíre doing? Back then we thought, "This seems possible. Why doníí we just do it?" But Suzuki Roshi knew that if you raise up a particle of dust youíre liable to raise up a whole cloud of dust. So this is like parents and children. Suzuki Roshi was like the parent, and we were like the children. The parent has understanding and maturity; the children just want to go ahead and do something. We still have this kind of problem. Suzuki Roshi came in 1959. In 1967 we bought Tassajara. In 1969 we bought the Page Street building, and in 1970 Tatsugami Roshi came to Tassajara and developed the monastic system that we now have. There were a lot of people at Zen Center at that time. Some people just wanted to develop a community style. So when we brought Tatsugami Roshi from Eiheijióhe had been Ino at Eiheiji for ten yearsóto set up the monastic system, it sepa-rated the people who just wanted to live in a commune from the people who actually wanted to practice at a monastery. That whole practice period we spent forming the doan-ryo, the tenzo-ryo, the rokuchiji, all of the systems that we now have. He taught us how to chant, how to hit the drum, how to serve. Before that time we had no formal training. I was shuso [head monk] with Tatsugami Roshi, and it was wonderful to practice with him. He didnít speak any English, I didnít speak any Japanese, but he would speak to me in Japanese and I would speak to him in English, and we seemed to understand each other. I donít know how that happens, but it does. Before Suzuki Roshi died we had lots of Japanese teachers. I can recall at least five Japanese teachers I directly practiced with at Zen Center, and it was a really wonderful time. All those teachers were so gracious and generous, and we really enjoyed their presence and enjoyed learning from them. After Suzuki Roshi died, Zen Center really took off. Katagiri Roshi and Chino Sensei had gone, and we didnít really have any Japanese teachers around. We decided to see what we could do on our own. So for twenty years weíve been practicing without Japanese teachers. Zen Center went psssshew! like a rocket, and then kapow! it crashed. Zen Center made a spec-tacular rise, and we wondered, "God, where is it going?" But it couldnít maintain itself because it didnít have the structure. It wasnít built to do what it did. And it just crashed. For four or five years the members scattered and the people who remained dealt with their grief. That was the dominant feeling at Zen Centerógrief. So in the last years weíve had a process of stabilization, and Zen Centerís doing pretty wellópicking up the pieces and trying to maintain a simple, thorough practice. Now here we are back again after twenty years, making some connection with our Japanese brothers and sisters. Weíve grown up a bit. Tatsugami Roshi used to say, "You are all baby bodhisattvas in a baby mon-astery." We used to enjoy that. "Yeah, weíre baby bodhisattvas in a baby monastery." Now weíve been out on the street. The kids have been out on the street, and had some hard knocks, learned a thing or two, and now we want to go back to our familial roots and say, "Hi. What can we do now? Is there any way we can continue together?" From my point of view thatís whatís happening at this moment. One of our questions is, what do we have to offer each other? When I think what can we give to our Japanese brothers and sisters, I canít think of any-thing. I feel kind of presumptuous or arrogant. If you have children, then you realize that children are your teachers. I donít know anybody with a kid that hasnít said, "This is my teacher." But the kid does not say, "I am my parentsí teacher." Thatís presumptuous. So the kid can be the teacher, but the kid should not know that heís the teacher. If I say, "I have something to teach you, or give you," thatís assuming some kind of role. So really all I can give is my sincerity ... my dedication to practice. At a certain point kids always want to be left alone to do what they want. My son Daniel is almost ten, and whenever I tell him anything, he says, "Thatís obvious. Donít tell me something thatís obvious." So now I keep my mouth shut and donít tell him anything. But I understand his position. He wants to stretch his own arms and legs, and find his own way. I have to let him make his own mistakes, with watchful guidance. And then when he hurts himself, he comes back to me because he knows Iím there for him. Daniel also used to say, "Letís go out and get some candy." And I would say, "No, we canít buy it. Candyís only for special occasions, and only a little bit." "Then why do they sell it?" (Laughter) Itís perfectly logical. Heís got his logic down. Why do they sell it if you canít just go out and buy it? But his logic is not tempered with experience. I feel sometimes that weíre perfectly logical in our assumptions, but our experience isnít always deep enough to temper our logic. So we have to be very careful. We want our candy, we want what we want, and there it is ... why canít we have it? Our practice is the practice of great patience. If we want something too much, this is what spoils our practice. It comes up in all of us. When I started to practice at Berkeley Zen Center, I decided that zazen was what I was doing. Every day I would sit zazen. If somebody wanted to sit zazen with me, that was wonderful. If nobody came, O.K. Feeling good, feeling bad, liking it, not liking it, it doesnít matter. If we have a flourishing Zen Center, great. If it falls apart, O.K. The main thing is, every day we just sit zazen. It doesnít matter where we are, or how we feel. Very simple practice. We donít like our practice to be complicated, but the more people we have, the more complicated it gets. How do we keep our practice simple in the midst of all these complications? And when we start relating to our Japa-nese brothers and sisters more closely, our lives will get more complicated. How can we keep our practice simple and pure? How do we meet? Where do we meet? Should we become more Japanese, or should the Japanese be-come more Western? We can simply respect our differences. We can honor our Japanese brothers and sisters for being Japanese, and they can honor us for being who we are. This is universal practice. It doesnít belong to anybody, but it belongs to all of us. When I was young, I was looking for my Jewish roots. I was looking for a Hasidic Jewish teacher, and I found Suzuki Roshi. And thatís what he was. (Laughter). Itís true. Iím sure that deep down he knew it, because where we met was the place where sectarianism or tribalism doesnít matter. You know, Jewish people are a tribe. Japanese people are a tribe. So tribal feel-ings create a barrier, and we can only go so far. I feel that in a certain way with Japanese Buddhism. But I also feel that Suzuki Roshi had crossed that barrier. It was no longer a problem for him. So we could enter into the same space. I could be me, and he could be him. And we could both include the whole world within ourselves. We need to trust each other, offer the best we possibly can, and really try to come to some pure synthesis which may take a long time. Nobody knows. Setcho in his verse says, "Let the elders knit their brows as they will." This means the old people who know a lot will say, "What are those youngsters doing? Are they doing the right thing?" They knit their brows. Setcho says, "Let them knit their brows as they will.... For the moment, let the state be established." A positive note. "Where are the wise statesmen and seasoned generals?" That means, where are the Zen masters and mistresses? Where are the leaders? Whoís going to do this? And then Setcho says, "The cool breeze blows. I nod to myself." This is a very important point. "The cool breeze blows" means whether it happens or doesnít happen, every day I sit zazen. If it works, great. If it doesnít work, O.K. I just do my best, and every day I sit zazen. This cool breeze means nothing can disturb us, we are not attached to anything. When we come to the zendo, we let go of everything. When we go outside, itís all new! Itís up to us. What do we want? In a way itís like being an illegitimate child. Does the illegitimate child want to be part of the family, and does the family want to accept the child as legitimate? And supposing that happens, how do we act? Does that mean the child takes on all the family customs? After youíve been out in the world, you may not want to take on all the family customs. You have your own customs. And does the family really want this ruffian running around the house? These are interesting questions. So all of this comes up with a speck of dust, but I feel very encouraged. The various facets of this gemóJapan, Europe, South America, all over the worldóhow do we make this gem shine? Weíve set up the Dharma. banner. Weíve raised the speck of dust. Weíre ready for new horizons. So we can make a big effort, but our effort should be to maintain pure practice. Thatís all. Iím really not asking us to do anything else, but all of us together to maintain pure practice. If we take care of Buddha, Buddha will take care of everything. As Maezumi Roshi was saying last night, quoting Dogen, "Just turn the Dharma, and then let the Dharma take care of it." We need this trust. We have to have this faith. This has been my experience, my direct experience. So letís not get fooled by anything, or overly ambitious. Just to learn how to let go and be together is enough. |

|