|

Dogenís fascicle, Zenki or Total Dynamic Working, was translated by Abe and Waddell with their explanatory footnotes. In the first footnote they write, "All dharmas (things) in the universe are the Buddha Dharma, and the Buddha Dharma is manifested or realized clearly in all dharmas." Technically, according to abhidharma teaching, a dharma (with a lower case "d"), is an aspect of experience, a feeling, emotion, thought, intention, or part of our form body. The early Buddhists put together various lists of dharmas that were most frequently encountered in human experience; which include thoughts, various feelings, and attitudes, which are wholesome, unwholesome, or neutral. Basically those are the dharmas, but actually in a wider sense, every manifestation can be called a dharma. And then, in another sense, Dharma with a capital "D" refers to Buddhaís teaching. When we say, the Dharma, it means the truth or reality of each of these individual dharmas, the dharmas with a small "d." The reality or the nature of our human constructs. So,"All dharmas, or things in the universe, are the Buddha-dharma." There is nothing left out, everything in the universe is Buddha-dharma. There are the several universes, there is one universe which is all encompassing and inclusive, and then there is the universe which is each one of us as an individual. Each one of us is a reflection of the whole universe, and the whole universe is contained within each one of us. And so, the question arises, where is the center of the universe? Does the universe have a center? If so, where is the center? In one sense you can say that the center of the universe is everywhere. If there is no particular center, then wherever you point can be the center. |

|

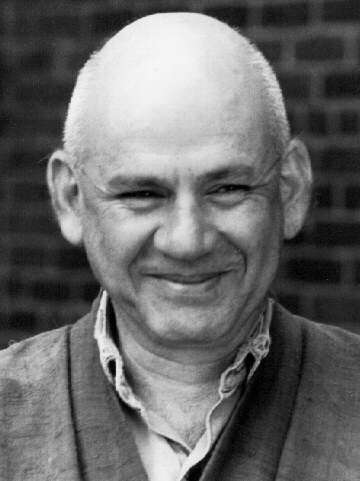

Sojun Mel Weitsman Roshi on Dogenís Zenki Talk Two of Three Talks Chapel Hill Zen Center, 2008 |

|

|

Wherever you are, wherever you stand is the center of the universe; but it doesnít mean that you alone are the center of the universe. Wherever anybody stands is also the center of the universe. So everything is standing in the center of the universe together, even though we are all in different places. So, "All dharmas or things in the universe are the Buddha-dharma, and the Buddha-dharma is manifested or realized clearly in all dharmas." So you can see that all dharmas are contained in the Dharma, Buddha-dharma. The Buddha-dharma is really about small, individual, particular things that have no inherent existence in themselves. For Dogen being confirmed by all dharmas is proven by the fact of oneself in zazen. It is emancipation from all attachments. It is a breakthrough that constitutes enlightenment. For all Buddhas, that is, for all enlightened beings, there is emancipation that is shedding of ego in practice and realization, manifesting or realizing in all dharmas oneís true self, a self beyond all duality. In other words, according to my understanding, what Dogen is talking about is proven or manifested in zazen. Itís experiencing the unity of the oneness, as well as the diversity, of all dharmas with the universe. So this is why zazen is called zenki or Total Dynamic Activity. Two related Japanese terms are," kikan," which is the motive force that makes each dharmaís existence what it is, and zenki or the universal activity that exists within each dharma or each manifestation. One day a monk asked Joshu, "Does the dog have the Buddha nature?" A great question. Joshu answered, "No." But, "no" used in a non-dualistic way. Another time when someone asked Joshu, "Does a dog have the Buddha nature?" He said, "Yes," but "yes" used in a non-dualistic way. In the same way I use "life" as a non -dualistic term that includes both birth and death. "No" in this case contains both yes and no. Absolute "no" has to contain its opposite. Ordinarily, we use yes and no in relative opposition. But when yes and no are considered in a non-dualistic way, yes contains no and no contains yes. Birth contains death, and death contains birth. So within each momentís activity of birth is also its death. Birth and death are happening at the same time, and in each moment. The birth of something is also the death of something, and the death of something is the birth of something. Otherwise, continuation couldnít happen. Emptiness in this sense means the space in which something can happen. Without emptiness everything would freeze as it is. In the same way if you look at birth and death in that light, death is necessary for birth or manifestation. If there was no death, there couldnít be any manifestation, and vice versa. If there was no manifestation, there couldnít be any death. So, zenki means to live (and love) each moment in full function right now, not clinging to existence and not wishing for death. Otherwise, we have a one-sided understanding of existence that is called an upside down view. When I studied this with Katagiri Roshi years ago, he had a picture of a little man in a circle upside down. Dogen wrote, "ĎEmancipationí means that life emancipates life, and that death emancipates death. For this reason, there is deliverance from birth and death, and immersion in birth and death. Both are the great Way totally culminated. There is discarding of birth and death, and there is crossing of birth and death." Dogen is saying, donít be attached to birth and donít be attached to death. Footnote 2comments on this, "Crossing birth and death and immersion in birth and death signifies entering birth and death in order to work for the salvation of all beings." For Dogen, one is totally immersed within birth or death while one is free from birth and death. But one stays within birth and death in order to help sentient beings to understand how to be free from birth and death. This is the bodhisattva ideal, the bodhisattva stays in the world of birth and death Ė the dualistic world of birth and death, in order to save all beings. And this is what the bodhisattva vow is all about; however, all beings might not want to be saved from this problem. Dogen continued, "When the great Way is realized, it is nothing but lifeís total realization, it is nothing but deathís total realization." Then he wrote, "This dynamic working readily brings about life and readily brings about death. At the very time that this dynamic working is thus realized, it is not necessarily large and it is not necessarily small; it is not limitless, it is not limited; it is not long or far, short or near. Oneís present life exists within this dynamic working: this dynamic working exists within this present life." In footnote 4 the translators comment, "Since the great Way of buddhas is beyond all dualities, including the basic duality of birth and death, from lifeís point of view each thing, including death, is lifeís total realization; from deathís point of view each thing, including life, is deathís total realization." We usually donít conceive of thinking or realizing in the realm of death, nor do we think in terms of manifestation. Dogen equated birth and death, and he set up death in a way that included manifestation. Birth and death are separate terms, but I think manifestation is good because it means existence, and death means non-existence. So, manifestation might be a better term in some ways, but heís using all three of these terms. Usually we donít see things from deathís point of view; we see things from the point of view of manifestation. Dogen said that since the great Way of buddhas is beyond all dualities, including the basic duality of birth and death, from manifestationís point of view, each thing, including death, is lifeís total realization. And from deathís point of view, each thing including manifestation is deathís total realization. It is also called "kikan" or the eternal now. Our present manifestation exists within this dynamic working, and this dynamic working exists within this present life. Life is not a coming and it is not a going Ė it is not an existing and it is not a becoming. Nevertheless life is the manifestation of the total dynamic working, and death is the manifestation of the total dynamic working. For Dogen, it is important to have what he calls "vow of practice," i.e. living by vow rather than living by karma. Most of us live by karma without realizing the working of cause and effect and how we reap the consequences of our self-centered actions. Living by vow is living according to the Dharma. When we understand the meaning of our vow of practice, it should help us understand the non-duality of birth and death. This is what Dogen called the Great Matter. This is why we say we are not searching for enlightenment; but when we simply sit zazen, enlightenment manifests without seeking it. We express Buddha dharma without trying; we are simply expressing the total reality which is zenki. So, zenki is the other side of birth and death and includes birth and death. The side which does not discriminate but which realizes birth within death, and death within birth. It means birth emancipates birth, death emancipates death. Footnote 6 explains, " This dynamic working is not something to which dualistic concepts can be applied." Dogen wrote, "This dynamic working readily brings about birth and readily brings about death. At the very time that this dynamic working is thus realized, it is not necessarily large, not necessarily small; it is not limitless, it is not limited; it is not long or far, short or near. Oneís present life exists within this dynamic working: this dynamic working exists within this present life." Dogen continued,"You should know that within the incalculable dharmas that are in you, there is birth and there is death. You must quietly reflect whether your present life and all the dharmas existing with this life share a common life or not. [In fact,] there can be nothing Ė not one instant of time or a single dharma Ė that does not share life in common. For a thing as well as for a mind, there is nothing but sharing life in common." I would like to read footnote 7, "Each existence has itís own respective dharma stage; itís own "time" and does not intrude upon any other existence. Yet that which makes each and every existence individual is also functioning equally within each and every individual. Because there is life, there is death; because there is death, there is life. Life is life and is not death, yet there cannot be life without death, and vice versa." In Dogenís text Genjokoan he wrote, "It is an established dharma teaching that life does not become death. Buddhism therefore speaks of no-life. It is an established teaching in the Buddha Dharma that death does not become life. Buddhism therefore speaks of non-extinction. Life is one stage of total time and death is one stage of total time. With winter and spring, for example, we do not say that winter becomes spring, or that spring becomes summer." We sometimes do say this, but according to reality, it is not correct. Spring is the total time of spring, it has its before and after and its present, and the same is true for winter. Dogen also wrote of firewood and ash. Firewood is the stage of being firewood, then when it burns, there is ash; but it is not that the firewood becomes ash. Firewood is a condition for ash. But we canít say that the firewood turns into ash Ė we do say that, but it is not correct. In 19th Century Zen Master Nishiari Bokusanís commentary on Genjokoan, he said, "If you asked tofu, ĎTofu, do you know that you were once beans?í Tofu would say, are you kidding? Those round, hard things? Iím flat and smooth." So, each dharma has its own conditions for making it what it is. Indian and Buddhist philosophers, say when you have a cow, you call it a cow. When it is slaughtered and you eat it, you call it meat. So you donít say, "I am now eating cow." You say, "I am eating meat." Steak is in the dharma position of being steak. Steak is not the same as a steer, although the steer is a condition for the existence or the manifestation of steak. (Transcribed by Mary Johnston) © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2015 |

|