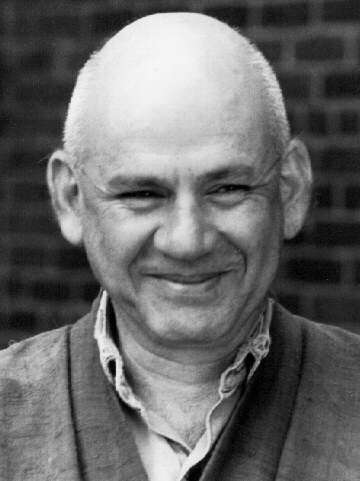

Heart Sutra Sesshin lecture given October 26,

1994 by Sojun Mel Weitsman |

I want to

talk about the lines, "With nothing to attain a Bodhisattva depends on Prajna

Paramita and the mind is no hindrance. Without any hindrance no fears exists. Far apart

from every perverted view one dwells in nirvana. In the three worlds [past, present,

and future] all Buddhas depend on Prajna Paramita and attain unsurpassed, complete

perfect enlightenment." Then it talks about the mantra, "...therefore

know the Prajna Paramita is the great transcendent mantra, the great bright mantra, is the

utmost mantra, the supreme mantra which is able to relieve all suffering and is true not

false." "With nothing to attain a Bodhisattva depends on Prajna Paramita and the mind is no hindrance." We call this practice the practice of no gaining. When Suzuki Roshi was teaching, that was one of his mantras: "no gaining mind." |

| He used to talk about it all the time as the fundamental aspect of our practice.

It was his shtick, actually. Whenever a student became egotistical, or asked,

"What about getting enlightenment?" he hit him with that shtick: no

gaining mind. It’s not that there is not enlightenment, but it is as Dogen says,

"Practice-Enlightenment." Without practice, we don’t talk about

enlightenment. Enlightenment doesn’t appear without practice, so practice and

enlightenment go together. Suzuki Roshi never talked about getting enlightened, and during

the period when he was teaching there were a lot of teachers, both Soto and Rinzai

teachers, who were driving the students to gain enlightenment during sesshin. You know,

someone is going to get kensho. But Suzuki Roshi didn’t believe in it. Instead

of emphasizing kensho or enlightenment, he always emphasized practice.

Enlightenment is this thing, the Grand Prize, that thing that people kind of want as the

reason for practicing. Buddha says, "You take the raft and go to the other shore, and, when you are on the other shore, you don’t need the raft anymore, so you let go of it," which is very logical. It means you practice in order to get enlightenment, and then, when you have enlightenment, you don’t practice anymore. Practice is just a vehicle for gaining enlightenment, or a means to enlightenment. Actually, though, practice is not just a means to enlightenment. Practice is a vehicle for expressing enlightenment. So instead of emphasizing the carrot, we emphasize the run to reach it. The activity itself is the important thing, not the final result of the activity. When we say "no goal," it doesn’t mean that we have no objectives or goal. In order to move in life, there’s got to be an objective. You are born, and then you go to school, and you go to school to learn enough to go to college. Then you go to college in order to learn enough to get a good job, and to have a career, and raise a family, and make a lot of money, and live happily ever after. But it’s not so happy. This is a goal oriented way of life, and is very usual. In practice, on the other hand, the goal is to come to where you are. It’s not like there is some place that you are going. The goal is to be where you are and allow enlightenment to express itself. We all have goals. For instance someone has to cook our meals for us during sesshin, so that person has to have some objectives, some goal, and the timing has to be just right. Every meal has to come out just on time. All the ingredients have to be right, and you can’t burn something. But within that goal of getting out a meal there is also every step of the meal, and in each step is concentrated activity. In other words, the practice of the cook is to be completely one with every activity, moment by moment. Even though there is some place to go, where the cook is, is right here doing just this. So there is no one step that is any more important than any other step. Each step, each activity, has the same quality, and the same concentration, and is given the same action as every other step. Our life is being led moment by moment, just like sitting on the cushion. That is why the cook’s activity during sesshin is all in the kitchen, but is still sesshin. It’s exactly the same as sitting on the cushion, even though the activity is different. It’s like dropping self, dropping ego, and just being one with activity moment by moment, except that there is some different orientation. This is how we should live our daily lives as practice. We get so caught up in the goal of activity that we don’t pay attention to where we actually are because we want to get somewhere. So we are always getting somewhere and we get lost in the getting somewhere, and forget the being inside. There is the "doing" side and there is the "being" side. The being side is just pure activity without any idea of accomplishment or goal. Within our goal, our activity is just being, but with no goal. But we always have to do something. Even when we are sitting on the cushion we have to do something. So there is doing and being in that activity. When we sit, we should put all of our whole body and mind on the cushion. Whole body and mind being present in great dynamic activity. That’s why we need a certain posture, good posture, and with a lot of energy, and at the same time we let go of the tenseness in our body. There is a certain amount of tension that is necessary for any structure to have integrity, but what is extra is all that tension that builds up. Sometimes I see it as a kind of fountain. The energy is going up and is also falling down without any effort. It’s a cycle of energy: the energy is moving up very strongly and falling down very gently. There is this effort, but it is just pure effort, pure existence...just experiencing pure existence. No desire, no self, actually, just letting go of self and allowing the universe in. I think of zazen as an offering: presenting ourselves to the universe. This is our complete, total offering to the universe. Zazen is presenting ourselves with our best posture, and our best energy, and nothing held back. The universe penetrates and permeates our whole being. There is no gap. "With nothing to attain..." There is no attainment here. Enlightenment, light emanates from this activity, but it doesn’t have any special color or shape. Komyo, Komyo-zo. Komyo means "radiant light," and Komyo-zo is "samadhi of radiant light," which is zazen, enlightenment. This is why we can say we begin practice from enlightenment. We don’t practice in order to get enlightenment; practice starts from enlightenment. Practice proceeds from enlightenment, and in our daily lives is a kind of gradual practice. From enlightenment our life proceeds with gradual practice forever. There is no hindrance. "With nothing to attain, a Bodhisattva depends on Prajna Paramita," depends on the "perfection of wisdom," depends on this source of light, depends on emptiness, which is depending on nothing. Depending on nothing means depending on everything because emptiness is interdependence. Form is emptiness and emptiness is form. What do we depend on? What do I depend on? That’s the big question. What do we all depend on? If we realize that everything is everything, no fears exist even though you may get scared. Of course, we get scared, but, ultimately, there is no need to fear because, whether you like it or not, whether you are good or bad, what is going to happen to you is inevitable. How can we fear the inevitable? You just open to it. That is the ultimate zazen. "With nothing to attain a Bodhisattva depends on Prajna Paramita and the mind is no hindrance. Without any hindrance no fears exist. Far apart from every perverted view one dwells in nirvana." I can’t remember exactly what the Perverted Views are, but "perverted view" is to think that there is a self when there is no self, and to think that you are in a happy state, or something like safe state, when it is not safe at all. Mistaking what is for what isn’t, and mistaking what isn’t for what is. It’s called upside down views. Then, at the end of the Sutra, it talks about the mantra. "In the three worlds [past, present, and future] all Buddhas depend on Prajna Paramita and attain unsurpassed, complete, perfect enlightenment. Therefore know the Prajna Paramita is the great transcendent mantra...." So, what is a mantra? We think of a mantra as a few words that you repeat over and over, but mantra is like our activity. A true mantra is not just repeating some words over and over, but the way we actually move in our lives is our mantra. Our practice is our practice. The Prajna Paramita mantra is the mantra of practice. In a narrow sense, it’s how we enter the zendo every morning and sit on the cushion, chant the sutra, and bow, and move. This way is actually "mantra," the mantra which induces prajna. When we offer incense we invite prajna to permeate our activity, and we invite Buddha to join our practice. If you look at the rhythm of our life, no matter how rough or smooth our life is, there is always a rhythm, some kind of rhythm, and the rhythm of our life is the mantra that we are always reciting. So, what kind of mantra do we want to recite? How can we recite this mantra which induces prajna through our activity day after day? I used to watch Suzuki Roshi’s activity, you know. When I first started to practice, I remember that I was amazed because my life was so loose and I came to the zendo and I saw this little guy who would come out his office every morning, offer incense and bow, and sit on the cushion, and do zazen, and all the things that you do, and then go back to his office. At the end of zazen, we would file out and bow to him on the way out, and he will always look at us and bow. Every time I went to the zendo he was there, and he did that. I thought, "Well, he does this two times every day and he doesn’t seem to get tired of it." His activity was so different from mine. In my activity, I never wanted it to repeat more than once or twice, but his life was this life of continuously doing the same thing over and over again, and bringing something extra to doing it, too, you know. I realized that the way he lived his life was like a mantra. The activity of his life was very narrow, but, within that narrow parameter of his life, his life was very rich and satisfying. He didn’t need to occupy himself with other things to entertain himself. He had complete satisfaction from doing what he did completely. It was very impressive. That is our mantra, our practice. "So proclaim the Prajna Paramita mantra..." through our activity. We don’t chant this mantra very much, except during service when we recite the sutra, but the mantra goes on in our life day after day. © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 1999 |

|