|

Part I We are not trying to get something good. Weíre not trying to get something bad. Weíre not trying to get anything. Weíre just giving ourselves to ourselves .... And thatís a wonderful kind of gift. Itís really nice to be back in Chapel Hill and see all the many familiar faces, as well as lots of new faces. Thereís something about this place, I think, that breeds potential Zen students. So itís quite a unique place. As you may know, Pat was the director of the City Center in San Francisco before she moved to Chapel Hill, after practicing for 20 years at the San Francisco Zen Center. She and Tom and Dhyana have been here for not quite two years, and have begun to establish this wonderful place with the help of many of you, and I feel very good about the way that people are responding. It takes time to establish a practice place, and sometimes there is a lot of enthusiasm in the beginning, and sometimes the enthusiasm wanes for one reason or another, and then surges back. Sometimes you think youíre doing very well, and then everything looks like itís gone, and then it will come back again. This kind of rhythm is normal. To establish a practice place in a strong way takes a lot of time and it takes a lot of effort from the sangha. I remember when Suzuki Roshi asked me to start the zendo in Berkeley. I found an old Victorian house and thought, "Iím just going to sit zazen every day." And every morning I got up and sat zazen and if somebody came, that was wonderful. If nobody came, that was okay, too. My practice is just to sit zazen. But someone else always came, too, and little by little, we had a community of practitioners or a sangha. It took many years before the sangha actually matured but after a number of years, there were many strong members. |

|

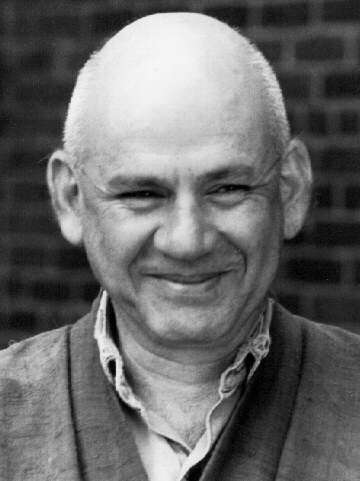

We Are Not Trying to Get Something Good

Sojun Mel Weitsman Talk given to the Chapel Hill Zen Center, March, 1993 |

|

|

We started in 1967 and after

twenty-six years, we still have some of our first members practicing very

strongly. They have seen us through many changes and many phases, and I

think that kind of support really creates something wonderful. So, I hope

that here, we can have that kind of good feeling Ė I really feel that Pat is

a wonderful priest, and if you give her your support, she will give you

everything she has. That I know. I think one thing that makes a sangha work is one dedicated person Ė one person who, no matter what anybody else does, is just dedicated to doing this practice. Through that dedication and continuous practice, things work. The other thing that makes things work is people taking responsibility for the practice and the zendo. As soon as you take responsibility, you become part of the sangha. Our center in Berkeley is more than just a house Ė itís a zendo, a community space, and residence. But every person who is a member of the sangha has something to do to take care of the place itself. So, someoneís job may be just to keep a room neat. They straighten up this room, or they keep the altar clean, or sift the ashes, or do something else Ė just one thing, but these little things add up and that responsibility ties us all into the way everything works. The way the sangha works is for all the members to take some responsibility to see that it works. Then everyone feels grateful for everyone else and feels, "Iím supporting your practice, youíre supporting my practice." Otherwise, a few people may be doing everything while everyone else just comes and goes, which isnít so good. Nothing works that way. As a lay community, we sit together and we study together, but we lead our lives separately. But when we come together and do this practice, there is a kind of cooperative, mutual support that is most valuable. Itís important for everyone to figure out, "What is my practice?" "How can I do this practice?" "What is it that I can do that actually creates a practice for me?" We have Zen philosophy and we have Zen doctrine and we have Zen this and that, but the important thing is how to practice. How do we actually put our behind on the cushion? Or if we canít sit cross-legged, then how do we sit in the chair or some way that works for us? Thatís the bottom line (no pun intended). I think the community is shaped a lot by geography. In Berkeley you can get anywhere in ten or fifteen minutes, from one end to the other. But the sangha here is spread out. So you have a different kind of configuration to deal with, and you may have to drive thirty minutes to get here. So you have to figure out what kind of practice works for everybody. At the Berkeley and San Francisco Zen Centers, we are used to daily practice. We get up early in the morning and zazen begins between 5:00 and 6:00, and there is zazen again before dinner. Iíve seen other practice places where everybody liked to sit at night. Thereís something about a place and the people that create a way of practice. You have to feel out, whatís the most convenient way for everybody to practice together. I donít know what that will be here, and I donít want to say what it could be or should be, but I think you have to find that out Ė we all have to find that out. The two sides weíre dealing with in our practice is how to practice zazen and how to practice in our daily life. I suggest that you take a certain period of timeĖit could be a week, it could be two weeks, it could be a month, or six monthsĖbut in that time period you look at your calendar and decide, "Iím going to sit this time every week." It may be one day a week, it may be five mornings, it may be two afternoons, or whatever. You decide that this is what Iím going to do, and this is the way Iím going to do it. This practice schedule fits in with my life. You have to take into consideration your particular responsibilitiesĖyour family, your school, or your workĖwhatever it is. And for that period of time, thatís your commitment. So you say, "Oh, thatís my commitment," or, "This is the time for me to go to zazen." Just like, "This is the time for me to go to work," or "This is the time for me to go to bed." "This is the time to sit zazen, because I said so." What it all hinges on is what your commitment is to yourself. The most important aspect of practice is your commitment, because you canít practice without some kind of commitment. When you sit zazen youíre committing yourself to sitting still for the period of zazen. To commit yourself to that is a very important factor. Then, zazen becomes an integral part of your life. If zazen is not an integral part of your life, itís not zazen because zazen is nothing more than the way you live your life. Suzuki Roshi used to say that Zen practice is living your life moment by momentĖliving your life completely, thoroughly, moment by moment. You have to be careful how you make your commitment. Many people have a tendency to overextend themselves. You may say, "Well, I will commit myself to sitting zazen five times a week." But if this is not realistic, you will become discouraged. Making your commitment carefully helps you make realistic commitmentsĖit helps to make your life realistic. An important part of Zen practice is to make your life realistic, to do things in a way that your life becomes real. After the week, or the month, or whatever period you chose, then you review how you did. "Did that work? Yeah." So you extend it another week or month. Or you change it, "No that didnít work so well." Or your life changes but you have the same commitment, and find your previous commitment is not longer working for you, so you get discouraged. But all you have to do is change your commitment to work with the way your life is now. This is why I suggest making the commitment for a limited period of time. That way you have a beginning and an end to a particular commitment, and itís very realistic. You keep experimenting until you find your proper rhythm, and itís up to each one of us to find out how to do it. If youíre in a monastery, you commit yourself to whatever the monastic schedule is, and you just follow that. But here, everyone has to make up their own practice schedule, and itís your responsibility to create it with your teacher. Itís good to go to your teacher and discuss your zazen schedule and what can be expected of you because sometimes the teacher thinks that youíre doing one thing while youíre doing something else. If the teacher doesnít know that, they maybe expect something from you that shouldnít be expected. So itís very good to keep in contact with your teacher and discuss your practice; and when you tell someone else what youíre doing, it makes your commitment more realistic. Practice needs that kind of intentional commitment because otherwise we practice based on the way we feel. You know, "Today I feel really good, wouldnít it be nice to sit zazen?" Or "Jeez, I just feel awful, life is terrible. What can I do?" These feelings are important, but if you only depend on your feelings, itís not a real practice because our feelings are not reliable. We depend on our commitment, or what we have determined. Then, if we feel good or if we feel bad, or no matter how we feel, we honor our commitment, and that takes it out of the realm of preference. Real zazen is when we practice without any preference. We are not trying to get something good. Weíre not trying to get something bad. Weíre not trying to get anything. Weíre just giving ourselves to ourselves in order to establish ourselves on ourselves. And thatís a wonderful kind of gift. Transcribed by Patti Fogg © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2007 |

|