|

In the Mumonkan, Case #45, Master Wu-tsu said, "Shakyamuni and Maitreya are servants of another, tell me who is that other?" Master Mumon comments. He says, "If you can see this other and distinguish him clearly, then it is like encountering your grandfather at the crossroads: you will not need to ask someone whether or not you are right. In this verse, Mumon continues, "Donít draw anotherís bow, donít ride anotherís horse, donít discuss anotherís faults, donít explore anotherís affairs." Itís a very short koan. Wu-tsu said, "Shakyamuni and Maitreya are servants of another. Tell me, who is that other?" Shakyamuni of course is the past Buddha, and Maitreya is the Buddha who will appear in the future and in between is, who?" ["Us," says a student.] The written character for the word "another" literally means "that one." So the koan could also be read as, "Even Shakyamuni and Maitreya are servants of that one." This has a slightly ambiguous meaning. "Another" is a more generic term, and "that one" points to someone in particular. So to whom does Buddha bow? To whom does Buddha make obeisance? Even Shakyamuni and Maitreya make obeisance or bow to that oneóthat "other." We just finished the Bodhisattva Ceremony where we acknowledge all of our past karma and renew our intention to practice. During the ceremony, we bow many times to the various Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Who are these Buddhas and Bodhisattvas? When we bow to Buddha to whom are we bowing? This is a question that always comes up when we give instruction to beginners. Someone will say, "Well, who are we bowing to?" And even after 10 years of practice someone will ask the same thing. A very good question. You are bowing to yourself. |

|

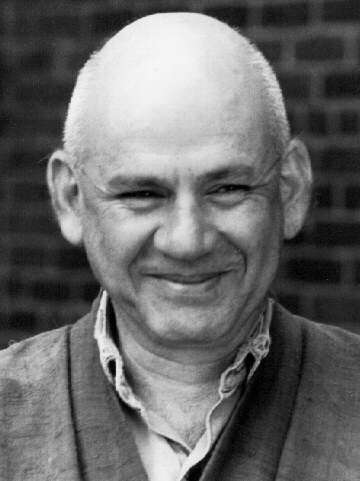

To Whom Do We Bow?

Sojun Mel Weitsman Talk given January 18, 1992 Reprinted from the Berkeley Zen Center March and April, 2002, Newsletters |

|

|

How do you bow to yourself? You canít see your own eyes, you canít see your own nose, we donít see our own face. Itís pretty hard to bow in this direction [toward ourselves], weíre always bowing in that direction [away from ourselves]. If you bow in that direction, you meet yourself. So who is this self? That question begs the other. If I bow to myself, then who is this "myself" that Iím bowing to? Therein is the fundamental koan, who is myself, and how do I bow to myself? The Buddha statue, the Buddha figure on the altar, is a kind of focal point. We make a beautiful Buddha figure in order to express our feeling about Buddha, but strictly speaking, Buddha is just an idea, a concept that we have. But behind Buddha is our true nature, so when we talk about Buddha, we shouldnít get it mixed up with some particular person or even some person from the past, who was born 2500 years ago. When we talk about Buddha we are referring to our own fundamental nature. So, to whom does Shakyamuni Buddha bow? In our lineage we say that when you have true understanding, you are the teacher of Shakyamuni Buddha. You are the teacher of Maitreya Buddha. As a matter-of-fact you are Shakyamuni Buddha. Who is Maitreya Buddha? Maitreya Buddha is like the messiah, comparable to the messiah in the West. When will this messiah appear? People are always waiting for somebody to do something. I was talking to somebody the other day who was dissatisfied with the state of Buddhism in America and in Japan and in Tibet. He said that we just keep going until some real leader appears. Thatís wonderful. But how will this religious leader appear? Who is your religious leader? There was a book about 10 years ago, which was kind of cute. The title was What To Do Till The Messiah Comes. One reason why we offer incense is to invite the spirit of prajna to come forth in our practice. When we have service, we offer incense to invite the spirit of prajna to arise. We ask Buddha to join our practice. We ask them to come and visit us, but nothing comes from outside to visit. It is just a way of evoking that spirit from within, because the spirit is no place else but here. Maitreya Buddha is nowhere else but here. Shakyamuni Buddha is no place else but here. There is no Buddha out there. No tushita heaven where Maitreya Buddha is waiting to come down. Maitreya Buddha is right here. Who is going to save us? Donít look around. Very often, when I talk to people about practice, they seem very discouraged. They say something like, "At first I had a lot of enthusiasm for practice, but now I wonder why am I doing this. I donít feel like Iím getting anything, and then I become kind of discouraged." Thatís right. If you have an attitude of wanting to get something, youíll be very discouraged because nothing will appear. This is the law of practice. If you want something, you will be disappointed. The second law of practice isÖ (Iím making this up [laughter])Ö The second law is: in order to make practice come alive, you have to give. You have to present yourself as an offering. You have to offer yourself completely to what youíre doing. Then, unexpectedly, something may appear. But you canít ask for it, and you canít expect it. You canít shake the tree and make the apple come down. Actually thereís only giving. Thereís also receiving, the counterpart of giving. So when you give yourself to the practice you stimulate generosity and then you receive something. You stimulate the nature of generosity. This is sometimes hard for people to understand when we simply want something. We want enlightenment, or we want to feel better. We want to improve ourselves, or we want to be calm or peaceful. These are good things to want. We want to be strong and imperturbable. These are all good qualities. Practice is not like going into the supermarket. "Iíll take some of these and some of those." You canít select the things you want. You canít just select the "good things" and put them in your bag, then leave the store. It doesnít work that way. Practice is like making a vow. I hesitate to say, "vow." So instead I usually say "intention." "Vow" is good, but I would not say to any of you that you should make a vow. If you want to practice you should have a strong intention to practice. Whatever your intention is, you should honor that intention. If you want a practice, then you should decide, for example, "Iíll sit zazen three times a week. Monday, Wednesday, Friday," or whatever. And then you put that on your calendar, and when the time comes, thatís what you do. If you donít honor your intentions, then itís hard to maintain a steady practice. There are so many competing activities being displayed before us, enticing us to pick them up, that if we donít maintain a strong way-seeking mind, we canít sustain the practice. If you think about all the things that you promised yourself you would do and didnít do, and look back on that, youíd be amazed at all the intentions you had that you didnít honor. Sometimes this holds us back. So thatís why we have such a thing as the Bodhisattva Ceremony. We avow all of our ancient karma and unrealized intentions, and renew and honor our intention to continue. This is one of the most important factors of practice, that you have an intention, and honor it. Everything else flows from there. Enlightenment, peace, itís all there in our intention. We also fall off, but when we fall off, we come back. As a matter-of-fact, weíre always getting sidetracked. Thatís the nature of our life: to have this intention, get sidetracked, and come back. One of the obstacles is, "Now that Iíve fallen off, I canít come back." Or, "Iíve been bad." So the nature of practice is to make the effort, that no matter what happens, to keep renewing or returning to our intention. Often one of the problems we have, is that we get caught up in our feelings. We always have to honor our feelings, but feelings are very fleeting. Theyíre not reliable. They can be just like foam. We can have a strong feeling, and then in the next moment itís a weak feeling. We can have a good feeling, and in the next moment itís a bad feeling. We can have a feeling about somebody thatís very sweet, and we can have a feeling about that same person in the next moment and itís very angry. These are just small examples. To be guided by feelings is very unreliable. What is reliable is our intention. When we rely on our intention, feelings will come and go. We have good feelings, bad feelings and undesirable feelings, but they donít carry us off of our path because our path is guided by our intentions. Thatís what makes practice difficult because we want to go with our feelings. People say, "When Iím happy I like to go to the zendo." Or, "When Iím feeling awful I like to go to the zendo because it makes me feel better." Practice is, no matter how Iím feeling, when itís time to go to the zendo and sit zazen, I go to the zendo and sit. Whether Iím feeling good or bad, laughing or cryingóhaving a good time or having a bad timeówhen itís time to sit zazen, let go of everything and at midnight you turn into a pumpkin. You just do what your intention is. And then we begin to see into the nature of feelings. We begin to be able to examine the true nature of feelings. We see how feelings come and go and are influenced by our ego. What makes us most unhappy, is trying to get happy. When we try to get happy, we become really unhappy, because even if we get happy for a little while, we get unhappy again. Then we try to get happy again. This continual effort to get happy makes us very unhappy. When people ask me, "How can I renew my practice, how can I sustain my practice, how can I feel encouraged in my practice?" I say, just renew your intention. Just follow your intention. Donít get pulled off by "Iím sleepy, or Iím lazy, or I found something really interesting to take up my time." These are difficult things to deal with in practice. Weíre going in the direction of practice and one day we wake up and realize that we are going in some other direction. We were going this way and suddenly, weíre going that way. "How did I get here?" We got here through either our intentions, or through our feelings, or through our delusions, because we create our life. We create our own life, in cooperation with the world around us, moment after moment. When we are off course though, itís possible to correct ourselves, itís possible to come back on course. But what is the course? What am I supposed to be doing? The best way to know what we are supposed to be doing is to head for the zero point. When you reach the zero point, then you can see all the way around, you have a good standpoint from which to view your life. But as long as we are standing on five, six, or seven, then everywhere we look, we only have a partial view. So itís really hard to get a broad perspective or to start from a new place. In practice weíre always starting from zero. It has no special shape or form. Our lives have no fixed shape or form, but when we step out and do something, we take on a shape and a form, and we give shape and form to our life. So practice, and our intention to practice, is to continually keep coming back to the zero point. This is the "no special" viewpoint, the viewpoint of impartiality. If we follow our intention, we can avoid falling into partiality. Partiality is influenced by, "I want, I donít want; I like, I donít like." As soon as I fall into, "I want, I donít want; I like, I donít like," I fall into partiality and canít see completely. This is a cause for suffering. Master Mumon comments, "If you can see this "other," or "that one," and distinguish him or her clearly, then it is like encountering your grandfather at the crossroads. You will not need to ask somebody whether or not you are right." "Encountering your grandfather at the crossroads," does not necessarily mean meeting your granddaddy, but meeting your true essence, your true face. In his verse, Mumon then instructs, "Donít draw anotherís bow, donít ride anotherís horse, donít discuss anotherís faults, donít explore anotherís affairs." In other words, rely on yourself. How do you rely on yourself? "Donít draw anotherís bow" means "do draw your own bow, do ride your own horse, do look at your own faults, and be careful about your own affairs." Mumon means that you should be very careful about your own affairs. So what is "drawing your own bow mean?" Drawing your bow is setting up your intention. What is your true course, and what will you follow? Decide, then once you decide, stay with it. Sometimes people say, "I canít make a decision, I donít know which way to go." But we have to make decisions, we have to go some way. Sometimes even making the wrong decision can be better than making no decision. Even if you make a wrong decision, you have a way to go. And then you have the opportunity to study your life from the perspective of that wrong decision and correct it. You have an opportunity to reach reality through your wrong decision. But we may think, "Reality is not what Iím looking for, what Iím looking for is happiness." If youíre looking for happiness, then you probably canít make up your mind. If youíre looking for reality, itís okay to make a wrong decision. Itís no problem, because you will fall into reality. Reality will hit you over the head. Better, of course, to make a good decision. But sometimes the wrong decision is the right decision. When you really have a good understanding of what is practice, then wherever you are, whatever you are doing, is the place of practice. If you have this understanding, whether you make a right decision or wrong decision, you have a way to go. "Donít ride anotherís horse." Yes. Ride your own horse. How do you ride your own horse? Whatís your effort? The horse is like the vehicle, an animal that makes it work. Hop on your own horse. Donít wait for someone and donít rely on someone else. Carry your own load. Make your own rhythm in life, but always in harmonious relation to your surroundings. In order to practice, we have to have some limitation, because the more we do and the more we have, the more watered down and superficial or shallow our life can become. When we have less to rely on, weíre forced to go deeper into our life. When we come to practice we have to put some limitation on our life. Itís like a bowl of water. If you put water into a flat dish it doesnít have much depth but if you have a nice deep bowl, it will hold a lot of water. It has form and some shape to it. Practice has to have some form and shape. It can hold some deep water, and when there are turbulent waves, there is a ballast of calm deep water. This is one of the things that people struggle with in our society because thereís so much opportunity. The curse of our society is that there is the overabundance of opportunity, and it keeps us strung out. The things that only a king would have had in the past, every one of us can have today. Itís amazing. The kings were some of the most distraught people because they had so much and had to protect it. Itís hard to put limitations on our self, but itís necessary. If we want to practice we have to put some limitation on our life. And this can be a big relief because then we donít have to run after everything we see. We donít have to own everything thatís advertised. One TV set might be enough. In the verse, Master Mumon says, "Donít discuss anotherís faults." Thatís right. Just look to yourself, examine your own life. Donít blame others for whatís happening to you. "You made me angry." No. "You did something and I got angry." "You walked by and made me fall in love with you." No. "You walked by, and I fell in love." In other words, take responsibility for your own feelings, take responsibility for your own thoughts and your own actions. Donít blame. If you can refrain from blaming, then you can examine yourself in a very clear way, no matter what, even if someone else is in the wrong. This is a very important point. Even if someone else appears to be at fault, donít fall into fault-finding. See if you can do that. See what that brings up for you. Donít explore anotherís affairs, just take care of your own life. Donít gossip, donít pick into someone elseís life. Just make sure that youíre doing the right thing. Make sure youíre following your own intentions. As the saying goes, if you want the tigerís cub, you have to go into the tigerís cave. If you really want something, you have to put yourself on the line. But better to just do it, without looking for something. This is one secret of practice. Dogen Zenji has a saying from the Genjokoan: "To study the Buddha Way, is to study the self. To study the self, is to forget the self." If you want to study yourself, you have to forget your self. This is Genjokoan. How do I study the self by forgetting the self? Another way of saying this is: to attain the Buddhadharma is to attain the self, and to attain the self, is to forget the self. According to Buddhadharma, there is no self. This self is not exactly a self. Itís a dynamic flowing of elements. A dynamic flowing of Buddha nature. There is nothing you can grasp. So to forget the self is to realize. It is to forget our idea of self, to forget our idea of who we are. Itís to turn toward our true self. The only way to do that is to not hanker after anything. Then we can see clearly who we are. And when we bow, we bow in gratitude. When we have some insight we bow in gratitude. That is all. We bow to our true self. Instead of trying to get something from practice, or from the Dharma, itís better to serve the Dharma. Buddha and Maitreya are servants of the Dharma. "It." What is the example of Buddha? To serve the Dharma, to serve truth, thatís all there is. When you serve, youíre fed. Iíll end with Dogenís story. He says, "To study the Buddha Way is to study the self and to study the self is to forget the self. Just to forget the self is to be confirmed by the 10,000 things. When actualized by myriad things, your body-mind as well as the body-mind of others drops away. No trace of realization remains, and this no trace continues endlessly." © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2002 |

|