|

In Zen, sometimes we talk about reality, or the way everything is, as being horizontal; and other times we talk about things as being vertical. In our life, the horizontal dimension is where everybody is the same–we are all in the same boat, on the same level, just people. The vertical dimension refers to hierarchy; and hierarchy simply means that each thing has its own dharma position–its own place in relation to everything else. The vertical dimension means simply that I am here, you are there; you are there, perhaps reaching down to the person below, and the person here is reaching up to the person who is up here. So everyone is helping everyone else, working together harmoniously with everyone. On the horizontal level, everybody is just the same, no matter what our position or what our function is. We have to understand both of these views. Sometimes people think, we should get rid of all hierarchy because we are all same. Well we are the same and there is hierarchy. Some people would like to get rid of equality, and just have the hierarchy. [laughter]. You have to have both and balance them. If you only have one or the other, it doesn’t work. Even if you eliminate all position, and simply have equality, someone will be above us. Hierarchy just happens because we are all different. In the Shobogenzo Zuimonki, Dogen Zenji talked about vegetarianism. I think it is kind of interesting the way he expresses this. |

|

Monastic Weekend Talk

Talk 1, part 2 |

|

|

“Just because disciplined behavior and vegetarian diet is to be maintained,

if you therefore insist upon these as fundamental, establishing them as

practice, and think that you can thereby attain the Way, this is also

wrong.” I don’t think that Buddha practiced that way in India. Also, in Southeast Asia and in Tibet the monks eat meat, it is part of their diet. I remember when I went to a conference of Buddhist teachers at Spirit Rock (in Northern California), there were Buddhist teachers from every tradition. They had a buffet, a vegetarian buffet for everybody, but the Tibetans had their own buffet. [laughter] You know pot roast, and … [laughter] So, Dogen said,

Eisai was Dogen’s first Zen teacher. Eisai brought Rinzai Zen to Japan from China, and Dogen studied with him in his last year. Then Dogen practiced with Eisai’s disciple, Myogen, and Dogen went to China with Mygen who became more of a teacher to Dogen than Eisai had been. One of Eisai’s students, Gogenbo, said, well, zazen is the thing. You don’t have to worry about chanting in the Buddha hall or being a vegetarian. There has always been this kind of question in Buddhism, whether to be a vegetarian or not. The Chinese monks were vegetarians. In China, vegetarianism was very strict, and also in Japan up to the Meiji era. In Buddha’s time, I believe, you could eat whatever was served to you, but you would not go out and kill a chicken and eat it. You wouldn’t go out and slaughter a cow and eat it, but if someone served you meat you would eat it, because it is something that was served to you. Monks like these don’t pick and choose their food. I remember U Silananda, who was a Burmese monk, who was around for some time at Green Gulch. People were standing in line to serve themselves lunch. Nobody had thought about it, and he was just standing there, and then I realized, he is standing there because, as a Burmese monk, he cannot serve himself; he was not allowed, in his tradition, to serve himself. So I said, “would you like something?” And he said, “Yeah.” [laughter]

So, in other words, this refers to the recitation, not to the meat eating.

He is saying that zazen includes all of these practices... to sit, to recite the scriptures all day long. I remember a Korean monk I knew in the 1960’s, Dr. Soo who made a big calligraphy which said, “The blue sky and the green mountain are the Zen sutra.” This gives the feeling that the way you live your life is reciting the scripture. You are creating the Lotus Sutra through your activity. You are writing the sutra through your activity. We also study the sutra, but to study the scripture all day long is simply input. So, how you express the practice is actually writing the sutra. The living sutra is zazen, and a little bit of chanting, and remembering and honoring and appreciating and acting out the practice in our life. “When sitting in meditation, what precept has not been maintained?” How do you maintain precepts when you are not sitting in zazen. That’s a bigger point. We are always sitting in zazen–sitting zazen is not just something you do on this cushion. Walking is zazen, eating is zazen, whatever we do, so we are creating the scripture with our life. Then he says,

In other words, if there is a reason for something, you shouldn’t just stick by the rule, you should be flexible, because the rule is to help us, not to hinder us, and if we need some other kind of help, we should be able to use that kind of help if we need it. But also, the demon was his sickness, so he is feeding the sickness. When he said he saw the demon on his head, he saw he was feeding the illness, he wasn’t feeding himself. I was at Tassajara in the summer of1970, and I was Suzuki Roshi’s attendant. One day he couldn’t find his eating bowl so he asked me to look for it. He said “I want you to look.” Everyone’s eating bowl looked the same, right? [laughter]. “I want you to go through the zendo and open up everybody’s oryoki bowls and see if they are mine.” [laughter] I had somebody help me because it was a big task, and, well, how do I know if they were his anyway? We couldn’t find his bowl. He said, “It must be because of the anchovies. In my salad I had some anchovies (somehow they were served to him). Maybe that is the reason my bowl disappeared.” [laughter] There is also the story of Suzuki Roshi and the student who was very proud of the fact that he was a vegetarian would’nt touch anything other than vegetables. When they left Tassajara, they went to a café and Suzuki Roshi ordered a hamburger and this guy ordered a vegetarian dish. When it came, Suzuki Roshi switched the plates. The reason he did that was, not because he didn’t like the fact that the person was a vegetarian, but that he was proud of being a vegetarian. It was the pride that was the problem. So he says, in effect, eating meat is not eating meat; not eating meat is eating meat. Meaning, if you are proud of what you do, if you have pride in what you are doing, that is eating meat. It is better to eat meat and not be proud of it than to not eat meat and be proud of it. Student 1: I have a question about the demon. The first time that I read

that, I thought that the demon signified the monk’s self-indulgence, which

was sort of odd because why did the abbot let him eat meat if he was just

indulging him? One of the legends about Huiko is that his arm was cut off by bandits. He seemed to have one arm. Why go to that extreme? It is an extreme story when you are willing to go through with it in order to achieve the way. I would not have tried to impress my teacher by cutting off my arm. He would be appalled and I think Bodhidharma would be appalled. [laughter] ...this cat brings me his arm, “Hey boss….” Oh, then Bodhi says, “well, you can be my student now.” [laughter] I think it is symbolic of cutting off the ego. “I’m willing to drop everything now” ... that’s the story. In an evening talk Dogen said,

This is like people who go to great lengths to do austere practice or flashy or impressive practice.

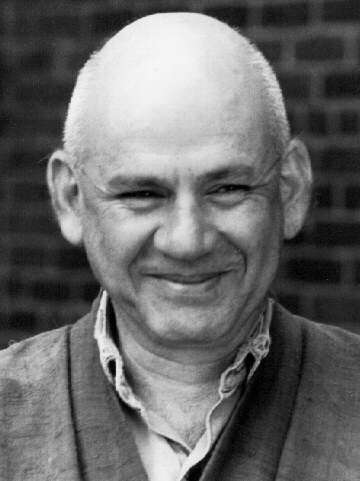

Even if people say something bad about you, continue your practice. When someone makes a derogatory remark about your practice or what you are doing, sometimes you may feel the specter of doubt rise up. “Maybe they are right. Maybe I should do something else.” One should be very firm in the Way in order to not be upset in the face of criticism, to be able to just continue without blaming or without feeling retaliatory. Even if doubt does arise, just continue; if you just continue, your confidence will arise. Transcribed by Mary Johnston © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2011 |

|