|

Often one of the problems we have, is that we get caught up in our feelings. We always have to honor our feelings, but feelings are very fleeting. Theyíre not reliable. They can be just like foam on the ocean. We can have a strong feeling, and then in the next moment itís a weak feeling. We can have a good feeling, and in the next moment itís a bad feeling. We can have a feeling about somebody thatís very sweet, and we can have a feeling about that same person in the next moment and itís very angry. These are just small examples. To be guided by feelings is very unreliable. What is reliable is our intention. When we rely on our intention, feelings will come and go. We have good feelings, bad feelings and undesirable feelings, but they donít carry us off of our path because our path is guided by our intentions. Thatís what makes practice difficult because we want to go with our feelings. People say, "When Iím happy I like to go to the zendo." Or, "When Iím feeling awful I like to go to the zendo because it makes me feel better." Practice is, no matter how Iím feeling, when itís time to go to the zendo and sit zazen, I go to the zendo and sit. Whether Iím feeling good or bad, laughing or cryingóhaving a good time or having a bad timeówhen itís time to sit zazen, let go of everything and at midnight you turn into a pumpkin. You just do what your intention is. And then we begin to see into the nature of feelings. We begin to be able to examine the true nature of feelings. We see how feelings come and go and are influenced by our ego. What makes us most unhappy, is trying to get happy. |

|

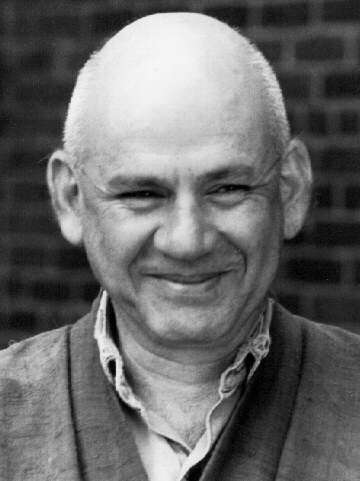

To Whom Do We Bow? Part 2 March, 2002, Reprinted from the Newsletter of the Berkeley Zen Center |

|

|

When we try to get happy, we become really unhappy, because even if we get happy for a little while, we get unhappy again. Then we try to get happy again. This continual effort to get happy makes us very unhappy. When people ask me, "How can I renew my practice, how can I sustain my practice, how can I feel encouraged in my practice?" I say, just renew your intention. Just follow your intention. Donít get pulled off by "Iím sleepy, or Iím lazy, or I found something really interesting to take up my time." These are difficult things to deal with in practice. Weíre going in the direction of practice and one day we wake up and realize that we are going in some other direction. We were going this way and suddenly, weíre going that way. "How did I get here?" We got here through either our intentions, or through our feelings, or through our delusions, because we create our life. We create our own life, in cooperation with the world around us, moment after moment. When we are off course though, itís possible to correct ourselves, itís possible to come back on course. But what is the course? What am I supposed to be doing? The best way to know what we are supposed to be doing is to head for the zero point. When you reach the zero point, then you can see all the way around, you have a good standpoint from which to view your life. But as long as we are standing on five, six, or seven, then everywhere we look, we only have a partial view. So itís really hard to get a broad perspective or to start from a new place. In practice weíre always starting from zero. It has no special shape or form. Our lives have no fixed shape or form, but when we step out and do something, we take on a shape and a form, and we give shape and form to our life. So practice, and our intention to practice, is to continually keep coming back to the zero point. This is the "no special" viewpoint, the viewpoint of impartiality. If we follow our intention, we can avoid falling into partiality. Partiality is influenced by, "I want, I donít want; I like, I donít like." As soon as I fall into, "I want, I donít want; I like, I donít like," I fall into partiality and canít see completely. This is a cause for suffering. Master Mumon comments, "If you can see this "other," or "that one," and distinguish him or her clearly, then it is like encountering your grandfather at the crossroads. You will not need to ask somebody whether or not you are right." "Encountering your grandfather at the crossroads," does not necessarily mean meeting your granddaddy, but meeting your true essence, your true face. In his verse, Mumon then instructs, "Donít draw anotherís bow, donít ride anotherís horse, donít discuss anotherís faults, donít explore anotherís affairs." In other words, rely on yourself. How do you rely on yourself? "Donít draw anotherís bow" means "do draw your own bow, do ride your own horse, do look at your own faults, and be careful about your own affairs." Mumon means that you should be very careful about your own affairs. So what is "drawing your own bow mean?" Drawing your bow is setting up your intention. What is your true course, and what will you follow? Decide, then once you decide, stay with it. Sometimes people say, "I canít make a decision, I donít know which way to go." But we have to make decisions, we have to go some way. Sometimes even making the wrong decision can be better than making no decision. Even if you make a wrong decision, you have a way to go. And then you have the opportunity to study your life from the perspective of that wrong decision and correct it. You have an opportunity to reach reality through your wrong decision. But we may think, "Reality is not what Iím looking for, what Iím looking for is happiness." If youíre looking for happiness, then you probably canít make up your mind. If youíre looking for reality, itís okay to make a wrong decision. Itís no problem, because you will fall into reality. Reality will hit you over the head. Better, of course, to make a good decision. But sometimes the wrong decision is the right decision. When you really have a good understanding of what is practice, then wherever you are, whatever you are doing, is the place of practice. If you have this understanding, whether you make a right decision or wrong decision, you have a way to go. "Donít ride anotherís horse." Yes. Ride your own horse. How do you ride your own horse? Whatís your effort? The horse is like the vehicle, an animal that makes it work. Hop on your own horse. Donít wait for someone and donít rely on someone else. Carry your own load. Make your own rhythm in life, but always in harmonious relation to your surroundings. In order to practice, we have to have some limitation, because the more we do and the more we have, the more watered down and superficial or shallow our life can become. When we have less to rely on, weíre forced to go deeper into our life. When we come to practice we have to put some limitation on our life. Itís like a bowl of water. If you put water into a flat dish it doesnít have much depth but if you have a nice deep bowl, it will hold a lot of water. It has form and some shape to it. Practice has to have some form and shape. It can hold some deep water, and when there are turbulent waves, there is a ballast of calm deep water. This is one of the things that people struggle with in our society because thereís so much opportunity. The curse of our society is that there is the overabundance of opportunity, and it keeps us strung out. The things that only a king would have had in the past, every one of us can have today. Itís amazing. The kings were some of the most distraught people because they had so much and had to protect it. Itís hard to put limitations on our self, but itís necessary. If we want to practice we have to put some limitation on our life. And this can be a big relief because then we donít have to run after everything we see. We donít have to own everything thatís advertised. One TV set might be enough. In the verse, Master Mumon says, "Donít discuss anotherís faults." Thatís right. Just look to yourself, examine your own life. Donít blame others for whatís happening to you. "You made me angry." No. "You did something and I got angry." "You walked by and made me fall in love with you." No. "You walked by, and I fell in love." In other words, take responsibility for your own feelings, take responsibility for your own thoughts and your own actions. Donít blame. If you can refrain from blaming, then you can examine yourself in a very clear way, no matter what, even if someone else is in the wrong. This is a very important point. Even if someone else appears to be at fault, donít fall into fault-finding. See if you can do that. See what that brings up for you. Donít explore anotherís affairs, just take care of your own life. Donít gossip, donít pick into someone elseís life. Just make sure that youíre doing the right thing. Make sure youíre following your own intentions. As the saying goes, if you want the tigerís cub, you have to go into the tigerís cave. If you really want something, you have to put yourself on the line. But better to just do it, without looking for something. This is one secret of practice. The koan "mu" is one of the fundamental koans, maybe the first koan many Zen students receive. If you understand "mu," youíll have kensho. But if you recite "mu" all day long with the idea of having kensho, it wonít work. If you think that by sitting zazen youíll become enlightened, you will be waiting a long time. Just sit. Dogen Zenji has a saying from the Genjokoan: "To study the Buddha Way, is to study the self. To study the self, is to forget the self." If you want to study yourself, you have to forget your self. This is genjokoan. How do I study the self by forgetting the self? Another way of saying this is: to attain the Buddhadharma is to attain the self, and to attain the self, is to forget the self. According to Buddhadharma, there is no self. This self is not exactly a self. Itís a dynamic flowing of elements. A dynamic flowing of Buddha nature. There is nothing you can grasp. So to forget the self is to realize. It is to forget our idea of self, to forget our idea of who we are. Itís to turn toward our true self. The only way to do that is to not hanker after anything. Then we can see clearly who we are. And when we bow, we bow in gratitude. When we have some insight, we bow in gratitude. That is all. We bow to our true self. Instead of trying to get something from practice, or from the Dharma, itís better to serve the Dharma. Buddha and Maitreya are servants of the Dharma. "It." What is the example of Buddha? To serve the Dharma, to serve truth, thatís all there is. When you serve, youíre fed. There is the old story of the long chopsticks. What is the difference between heaven and hell? In hell, there are people seated at a long table, and they have a wonderful meal piled up on the table, but they have these long chopsticks. The chopsticks are so long that when they pick up the food they canít get it to their mouths. Heaven is exactly the same place, same people, same food, and same chopsticks. But when they pick up the food with the chopsticks they put it into the mouths of the people on the other side of the table. Iíll end with Dogenís story. He says, "To study the Buddha Way is to study the self and to study the self is to forget the self. Just to forget the self is to be confirmed by the 10,000 things. When actualized by myriad things, your body-mind as well as the body-mind of others drops away. No trace of realization remains, and this no trace continues endlessly." Commentary Thoughts from Sojun, March, 2012 The basic understanding of Soto Zen is that ordinary beings and Buddhas are not two. So we have to investigate what is meant by "ordinary" and "Buddha." Since we speak of Ordinary and Buddha, they are two things. But the understanding is that they are one. Although this is a basic understanding, what does it really mean for our daily life? One day as I was sitting in my office my eyes fell on my bicycle as it was leaning against the wall, and my gaze wandered to one of the wheels, and I saw it as a mandala. The axle, the hub, as the center, and the spokes radiating in all directions, and attached to the spokes, the rim with its tire (for absorbing the hard knocks). Circles and cycles are fundamental in describing Buddhist understanding, and especially in Zen. There are the ox-herding pictures, Tozanís five ranks, Isanís one hundred circles, and in early Buddhism we have the twelve links of conditioned co-arising. The Tibetan model pictures the hub of the wheel of karmic life as greed, ill will, and delusion as characterized by the pig, the chicken, and the snake, and they are known as the three poisons. There are six spokes emanating from the hub that divide the six worlds, or realms: heaven, hell, fighting demon, human, hungry ghost, and animal. The rim that binds it all together is made of the twelve nidanas, or karmic conditions that continuously turn the wheel and lead to suffering. So this wheel, as it is, illustrates the human condition when turning on the three poisons and driven by karma and self-centeredness. The pig, the chicken, and the snake are symbols of self-delusion, which include greed and ill will and are the basis for ordinary human suffering. So in order to free our self from turning and being turned by our karmic life, we center our self on Buddha. We make a shift, and become Buddha-centered rather than self-centered. We offer our self to Buddha. This is renunciation. With Buddha as the hub of the mandala we are illumined from within and the six worlds become our fields of practice. This is the freedom of living by vow instead of being pulled around by karma. This is the meaning of ordination and the vow to save all beings. Even after taking our vow, we will still find our self shifting back and forth. This can only reinforce our determination for true practice. (Second of two parts) Reprinted from Berkeley Zen Center Newsletter, © Copyright Sojun Mel Weitsman, 2012 |

|