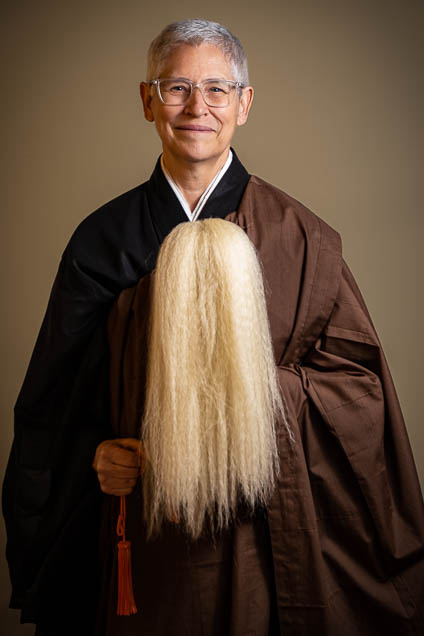

Examining Samantabhadra |

Some years ago during sesshin, I began wondering about Samantabhadra Bodhisattva. During our formal oryoki meals in the zendo, we chant the names of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas which includes Samantabhadra, the shining practice bodhisattva. I realized that there are not too many other times this bodhisattva is mentioned compared to Avalokiteshvara or Manjushri. I remember my sewing teacher and former Abbess of the San Francisco Zen Center, Zenkei Blanche Hartman, used to talk about Samantabhadra as her favorite bodhisattva. I associate Samantabhadra, as I do Zenkei, with diligent practice. In Taigen Leighton’s book, Faces of Compassion, he has a chapter that presents a very full picture of Samantabhadra. This book has thorough descriptions and histories of the major bodhisattvas, and he explains their relevance to us today. Taigen said, “A bodhisattva, carrying out the work of Buddhas, vows not to personally settle into the salvation of final Buddhahood until she/he can assist all beings, throughout the vast reaches of time and space to fully realize this liberated experience.” Taigen introduces Samantabhadra as “the bodhisattava of enlightening activity in the world, representing the shining function of wisdom. And that she embodies the luminous web of interconnectedness of all beings, similar to Indra’s net. Her name means ‘Universal Virtue’ or ‘Worthy’.” Taigen said, “Samantabhadra and Manjushri are often paired as attendants on either side of Shakyamuni Buddha, with Manjushri on his lion representing the essence of wisdom, and Samantabhadra mounted on an elephant, representing the application of wisdom actively benefiting the world.” Taigen said, “riding majestically on her slow mount has a feeling of calm, deliberate activity, imbued with clear intention.” In our lives she can be an example to inspire us to be beneficial in our community. Suzuki Roshi’s disciple, Jakusho Kwong, said that he placed a statue of Samantabhadra in the entryway to the zendo, “to remind us...of the importance of uninterrupted training in the practice of ‘just sitting.’ Samantrabhadra is the patron of the Lotus Sutra and known to have made the 10 great vows that are the basis of the bodhisattva (vows). Typically she is shown riding a white elephant with six tusks symbolizing purity, wisdom, and the power to overcome obstacles on the path to enlightenment.” Samantabhadra is described as being particularly radiant. She is described in a variety of ways. She may have long flowing hair and robes, or hair in a topknot as in early India. Her/his hands may be in gassho or holding a lotus, sutra scroll, teaching staff, or sword. “There is a rare depiction showing her/him with 20 arms holding implements to help beings.” In our temple our focus is our daily Zen practice, primarily just sitting zazen. Magical icons are not emphasized, and we hardly mention Samantabhadra. If you find it difficult to relate to these stories, I hope you find inspiration by thinking of the beneficial intentions embodied in this bodhisattva. My hope is that our practice can be inspired by bodhisattvas to bring positive energy into our practice and into our daily lives. Other than shining radiance, Samantabhadra is known for her set of ten vows. These are, “venerating buddhas; praising buddhas; making offerings to buddhas; confessing one’s own past misdeeds; rejoicing in the happiness of others; requesting buddhas to teach; requesting buddhas not to enter nirvana; studying the Dharma in order to teach it; benefiting all beings; and transferring one’s merit to others.” Taigen continued, “Samantabhadra’s first three vows, venerating, praising, and making offerings to buddhas, show the aspect of bodhisattva practice of our devotion to awakening and to those who have actualized such awareness.” They are a way for us to express our humility and heart felt gratitude. I think that feeling and expressing our gratitude is a good place to begin. In the zendo practice here, we primarily express our gratitude by chanting and bowing. We pay homage to Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, in the meal verse, in the monthly Bodhisattva Ceremony, and in the Lay and Priest ordination ceremonies. Sometimes when people come to Zen Center, they might be uncomfortable with the practice of bowing, or wonder why we are bowing to the statue on the altar. Many of us grew up in churches and synagogues and were taught that bowing to idols is a sin. But that isn’t what we are doing. We are not bowing to an idol of Buddha, because we are not bowing to a god outside ourselves. We are Buddha. The Buddha figure on the altar represents an example of practice, still sitting, a path to awakening, a way of life based on Buddha’s example and teaching. Taigen said, “We might also make the mistake of believing in a ‘perfect teacher,’ that our enlightened teachers can do no wrong. But we need to see that our teachers are worthy spiritual guides that have greater experience. And Teachers have the responsibility to reveal their humanity to their students. Images of buddhas or bodhisattvas represent awakened qualities in ourselves.” The third vow is making offerings to buddhas, and Taigen said, “Buddhist legend stresses that the spirit of the offering is much more important than the quality or quantity of richness of the offering. Sincere offerings to a buddha of a piece of fruit...have been highly praised and considered the cause of great resulting benefits.” In a former life, as a young child, Ashoka was supposed to have sincerely given Shakyamuni Buddha a mud pie. The Buddha gratefully accepted the child’s offering and took it back to add to the sand being used to construct a wall of his monastery, resulting in Ashoka’s later kingship. With a devotional attitude, “we can offer buddha a beautiful sunset, drifting clouds, and wildflowers...or our efforts to act with kindness.” Samantabhadra’s fourth vow is to confess his own past misdeeds. We can only awaken to our radiant nature by examining and acknowledging our mistakes, and the self-grasping nature of the conditions that prevent us from realizing our deeper reality. The best example of this confessing may be in the Bodhisattva Ceremony. We begin by chanting, “All my ancient, twisted karma, from beginningless greed, hate, and delusion. Born through body, speech and mind, I now fully avow.” This verse is also chanted in the lay precepts ceremony, in priest ordination, and in the wedding and funeral ceremonies. We publicly acknowledge our failings and mistakes. To see and acknowledge is the first step. Apologizing when we have caused harm is a good way to make amends and then let it go. “Samantabadhra’s fifth vow is rejoicing in the happiness of others, and in others’ virtues.” Taigen said, “When a bodhisattva realizes non-separation from others, their sincerest wish is simply that all beings be happy.” We chant the Lovingkindness Metta Sutta which states, “May all beings be happy.” Taigen said, ”Seeing others enjoy their lives, and develop their capacity for bringing joy to others is what truly gives Samantabhadra the greatest pleasure.” Yet, we are human. So even this simple wish can be challenging. Feelings of envy can arise when you see another’s good fortune and opportunity. But these feelings arise when we see others as ‘other’ because of our habitual dualistic thinking. When we free our thinking from our judgements, and try not to decide if someone else deserves their good fortune, this frees us from our suffering. This vow includes seeing the virtue in others not only their faults. The Zen priest, Ed Brow,n told a story. When he was head of kitchen practice at Tassajara, he complained to Suzuki Roshi about how the kitchen staff were not paying attention and not listening to him. Ed did not receive the sympathy he expected, instead Suzuki Roshi told him, “It takes a calm mind to see the virtue in others.” “Samantabahdra’s sixth and seventh vows are requesting buddhas teach and not to enter nirvana.” Taigen wrote, “...these vows stress the value of a buddha’s presence in the world, because of it’s fragility. When Shakyamuni was first awakened...he thought that nobody would be able to understand what he had realized, and that he may as well pass away into nirvana right then.” But the Indian deity Brahama spoke to Shakyamuni “after his great awakening, convincing him to remain in the world in order to find ways to teach others.” We now know that, from Shakyamuni’s first students up to today, many people have been able to understand and embody Buddha’s teachings and teach others. The eighth vow is to study the dharma in order to teach. Taigen said, “Samantabhadra reads, recites, ponders, and questions the sutras and the traditional writings…in order to be ever more fully in accord with awakened compassion and wisdom…” She finds ways “to share her study with others, either by expounding the teachings…or by expressing it in daily activity...in a way that allows other students to inquire and learn about the practice…” “But the dharma Samantabhadra studies includes teachings not only from sutras, but available in everyday activity, in upright sitting, and from lotus blossoms, sunsets, and moonlight reflected on the ocean, as well as in fear, anxiety, and from old age, sickness, and death.” I have always been deeply influenced by our teachers in the way they express the dharma in the way they step, bow, sit, their way of being and moving in the zendo. I’ve watched Josho, with full attention carrying a cup, sutra book, or zafu with both hands. Samantabhadra’s ninth and tenth vows, are to benefit all beings and transfer one’s merit to others. Taigen said, “Carrying out the Ninth Vow, Samantabhadra does whatever is necessary to help beings, taking on complex roles in social settings for the sake of those who are suffering…. also recognizing the systematic problems of society that may produce suffering, and then finding ways of facilitating necessary changes.” Our sangha has been involved in visiting prisons and corresponding with inmates. We have helped the transition of released incarcerated people. Sangha members support the Interfaith Council for Social Services with time and food donations and participate in the Crop Walk each year. Taigen said, “Samantabhadra’s tenth vow of transferring merit,has a technical meaning that is common to all bodhisattva practice. Developed bodhisattva’s have the special power to extend the merit accrued from their own insight and compassionate activities to other beings.” In our chanting service we offer the merit to others in each Dedication. After chanting the En Mei Jukku Kannon Gyo, we dedicate the merit to the ease and well being of our great friends. After the Dai Hi Shin Dharni, we dedicate the merit to deceased priests and benefactors of the world, to members and supporters of this practice, and our great abiding friend who passed, and to all sentient beings. “Samantabhadra’s tenth vow means that she does not practice hoping to achieve such results.” “All practitioners take on this vow of transferring merit when they practice with the attitude of extending it’s benefits to others.” Let’s look at examples of Samantabhadra today. I want us to think of bodhisattvas not as magical beings, but as beings that inspire our practice and lives. Taigen encourages us to engage in situations that might benefit beings. There are numerous Buddhists and others that are addressing social issues and conflicts with their wisdom and compassion. Looking to human examples, Taigen said, “Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. remains one of the great American exemplars of Samantabhadra in our time.... Dr. King has most fully come to symbolize and embody in the national consciousness the struggles for social justice of that movement. With his indomitable spirit and willingness to speak of the truth and suffering of many people, he bravely persevered while facing numerous arrests and threats, culminating in his assassination.” “Dr. King’s example encouraged and galvanized many to live and act with hope for a promised land of justice and equality, which he saw in the distance, even if he could not enter himself....His celebrated dream of a just and harmonious ‘pure land’ in which the very mountains and valleys ring out freedom, included a vision of all people fighting for human rights, with nonviolence and dignity but also determination.” Taigen said, “...because Samantabhadra sees each part of the universe as precious and of equal value, he is sometimes designated as the bodhisattva of the environment. This is to see the world as an intricate, sensitive system in which all the parts are integral to the whole. Samantabhadra’s teachings are about guarding and caring for the world.” Another person that I think of is Sojun Mel Weitsman. His practice was authentic, not charismatic. When he visited I felt he was 100% present. On the surface seeming very ordinary, but in the moment, paying close attention. Until he became ill, he just kept sitting and teaching. At one point he was going to retire as abbot and eventually did, but as long as he physically could, he taught. At 90 years old, he was still ordaining students and giving Dharma talks. Zenkei Blanche Hartman was also an inspiration to me and the hundreds of students she taught to stitch Buddha’s robe. Her steady practice was very visible. Besides showing up everyday in the zendo to sit into her mid-80s and leading sesshins, she was also the head teacher for sewing Buddha’s robe. The number of stitches she made teaching the tiny namu kei butsu stitch for countless rakusu and okesa over the years is as numberless as the grains of sand in the Ganges River. She taught in a subtle way, letting a student discover their rhythm. When someone made a mistake, I watched her take a breath, examine it, and if necessary undo it, and then restart the person’s stitches good naturedly. Her calm, caring sewing practice inspired countless students. She taught many of them to be sewing teachers, who are now carrying on this tradition. I feel very fortunate to be among them. I hope in our lives, we can try to follow this diligent way of Samantabhadra. Copyright © 2025, Jakuko Mo Ferrell |