Enlightening the Shadow Demon,

Nourishing the Hungry Ghost:

The [Sejiki] Segaki Ceremony

by Shosan Victoria Austin

Following are excerpts from Enlightening the Shadow Demon, Nourishing the Hungry Ghost: The [Sejiki] Segaki Ceremony, by Shosan Victoria Austin, originally published in Wind Bell v. XXVII, n.2; Fall 1993 (p. 9-14), which describes this ceremony in further detail.

Note: Chapel Hill Zen Center is now using the name Sejiki Ceremony for the ceremony described in this article. We heard a couple of years ago that the name Segaki had become a derogatory term for homeless people. Sejiki means food offering, the Se is an offering or charitable deed and the jiki is food.

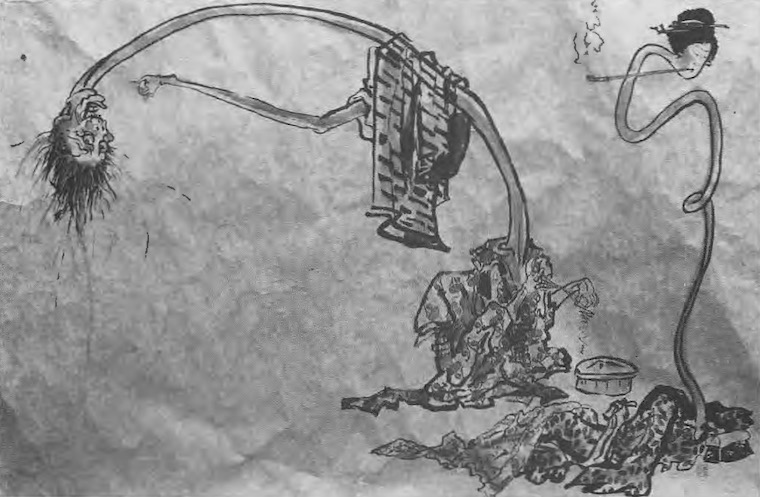

In Japanese, the word segaki means "feeding the hungry ghosts." The hungry ghost, or gaki, has a scrawny neck and a large belly — it has huge desires but is unable to take in nourishment. It is easy to think of hungry ghosts as a legend, an abstract idea, not us. But in fact, many of us, or people around us, are deeply hungry for nourishment. We all know times when we are unable to find sustenance in daily life. The se of segaki means the full range of nourishment, from regular food to the sustenance of Dharma.

At Zen Center, we started to do the ceremony at Kobun Chino Roshi's suggestion. He thought it would be helpful to us to have a deeper relationship with the negative aspects of our lives. Speaking to Rick Levine, Chino Roshi said the Segaki ceremony "makes a statement about... how to deal with negative things, negative happenings, negative parts of phenomena... For it is a kind of reminding ceremony, expanding your awakening to the darkness...Awareness is expanded to existence which is unseen, unknown, unthinked... Negative is another positive side. Awareness is already round and pure. [We can] expand our practice of compassion, in space as well as time. . . perhaps [with] this ceremony." *

For Segaki, we decorate the Buddha Hall with pictures of ghosts and demons, and the dining room with skeletons and jack-o-lanterns. We don't use the regular altar because the grandeur of the images might intimidate beings in the lower realms of existence. Instead, we make an inviting table at the rear of the hall and fill it with good food and water on attractive dishes. We hang banners around the special altar to make it inviting, and to dispel fear and doubt. Many people come in masks or costumes, both children and adults. The atmosphere and masking remove inhibitions and allow parts of us to be present that would not normally come to the Buddha Hall.

After the participants have entered the Buddha Hall, a procession winds its way down from the Founder's Hall. Some of the people in the procession might be in costume, others dressed in meditation clothes. The Doshi (presiding priest) carries a staff with metal rings that jangle with every step. Once the procession enters the Buddha Hall, everyone makes a low, spooky sound that swells to a roar, and then dies away. People use unusual instruments, including a Tibetan horn, a conch shell, party noisemakers, drums and flutes. The sound is meant to call all the spirits in the world, beings who might otherwise be afraid to come. The feeling is noisy and eerie, but calm and present. We repeat the call three times, to make sure that all the spirits are near. The Doshi walks slowly towards the special altar, making a statement: "Welcome, hungry ghosts. Be at ease, the vaguely known, the unconscious and unknown. Receive the best food. Welcome. Be safe." The Doshi offers incense at the special altar and recites a chant of homage to Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha in the ten directions. We also call on our original teacher, Shakyamuni Buddha; the great reliever of suffering, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva; and the revealer of the teaching, Ananda. This chant invokes the world of practice and awakening as the context in which it is possible for hungry ghosts to be held and nourished.

Then we chant the preface to the Kan Ro Mon, or "Gate of Sweet Dew." "Sweet dew" is amrta or nectar, the elixir of life. So Gate of Sweet Dew means the actual opening of the possibility of nourishment, even for the part of being that usually lacks the capacity to be fed. [Senior Dharma Teacher] Tenshin Anderson taught that this chant is offered in the context of the Bodhisattva vow, and of everyone's inmost request to release suffering through perfect wisdom and compassion. During the Kan Ro Mon, the Doshi says the mantras of the Buddhas and makes offerings of food and water to the ghosts, while praying that all the hungry and thirsty will be satisfied. The chant encompasses the entire range of experience, from profound suffering to profound samadhi. The Doshi says mantras that acknowledge food and water as the Dharma, that open the throats of the hungry ghosts, and that invite the spirits to return from whence they came, now satisfied.

The process of the ceremony-setting a protected space, inviting the shadow in a ceremonial space in which it can be safely held, and meeting it with everyday kindness through our Bodhisattva vow — is an enactment of our deepest compassion. In practice we have to be able to enter hell for the benefit of a suffering being, whether it's ourselves or someone else. We have to be able to be moved and have our practice continue. The deepest compassion is to feed the hungry and nourish the unsatisfied in body, speech, and mind, just when an opportunity presents itself. At Segaki, we activate the mind that can do this, and follow it with a rousing celebration of haunting and freedom, shadow and light.

* Unpublished notes by Arnie Kotler, from a tape of Kobun Chino Roshi speaking with Rick Levine, 1974.

|